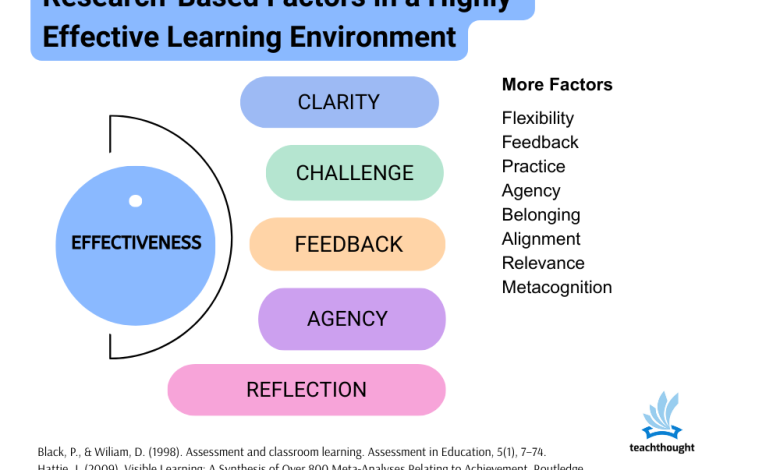

Research-Based Factors Of A Highly Effective Learning Environment [Updated]

Wherever we are, we’d all like to think our classrooms are ‘intellectually active’ places. Progressive learning environments. Highly effective and conducive to student-centered learning.

The reality is, there is no single answer because teaching and learning are awkward to consider as single events or individual ‘things.’

So we put together one take on the characteristics of a highly effective classroom through the idea of conditions. They can act as a kind of criteria to measure your own against–see if you notice a pattern.

Read more below.

Framework

A Conditions-Based Model for Highly Effective Learning Environments

A research-informed template for diagnosing learning environments and guiding lesson, unit, and program design across K-12 settings.

Abstract

Research on learning suggests that effective classrooms are shaped less by isolated strategies and more by the conditions under which learning occurs.

This model identifies five interacting conditions—clarity, challenge, support, agency,

and reflection—that constrain or enable the quality, depth, and durability of learning.

Definition

What ‘Conditions’ Means in This Model

A condition is a factor that enables or constrains the quality, depth, and durability of learning, regardless of the strategies or programs in use.

Conditions are not activities or techniques. They shape what is possible. When a condition is weak or misaligned, learning is constrained even when instruction appears strong.

| Condition | Operational meaning (what it must make possible) |

|---|---|

| Clarity

Direction |

Shared understanding of purpose and success criteria so learners can regulate effort and interpret feedback. |

| Challenge

Cognitive demand |

Cognitive demand that requires reasoning and productive struggle rather than mere completion. |

| Support

Persistence |

Persistence through difficulty via feedback, scaffolding, and a psychologically safe environment. |

| Agency

Ownership |

Ownership and motivation through meaningful influence over learning. |

| Reflection

Transfer |

Transfer, metacognition, and durable understanding beyond a single task. |

Conditions Matrix: Challenge × Support

The effectiveness of learning depends not on challenge or support alone, but on how they interact.

Reading it as a model: improvement comes from shifting conditions toward the upper-right quadrant, not by increasing a single factor in isolation.

Clarity

Direction

What clarity is

Clarity is shared understanding of purpose and success in learning: what is being learned, why it matters, and what quality looks like.

In effective environments, clarity is not something the teacher possesses, it is something learners can articulate, use, and act on.

Why clarity matters (mechanism)

Clarity functions as a directional constraint. When goals and success criteria are explicit, learners are better able to regulate their effort,

interpret feedback, and persist through challenge.

Indicators

- Students can explain the learning goal in their own words.

- Learners can describe what quality work looks like before completing the task.

- Questions focus on improvement and meaning rather than point values.

- Learners use criteria to evaluate work with reasonable accuracy.

Failure modes

- Students ask primarily procedural questions (e.g., grades, points, steps).

- Completion is mistaken for understanding.

- Feedback is ignored or treated as arbitrary.

- Students rely on teacher approval rather than internal criteria.

Research anchors: Black & Wiliam (1998); Hattie (2009)

Challenge

Cognitive demand

What challenge is

Challenge is the level of cognitive demand required to make progress in learning. It reflects how much reasoning, problem-solving,

and sense-making a task requires, not how busy or difficult it appears.

Why challenge matters (mechanism)

Challenge functions as a cognitive constraint. Tasks that are too simple produce little growth; tasks that exceed available support increase avoidance.

Learning is strengthened through productive struggle calibrated to readiness.

Indicators

- Tasks require explanation, justification, or problem-solving.

- Students grapple with ideas, not just procedures.

- Errors are treated as part of learning and revisited.

- Time is allocated for thinking, not only completion.

Failure modes

- Work emphasizes recall, formatting, or compliance.

- Students finish quickly with minimal understanding.

- Rigor is confused with workload rather than thinking.

- Engagement may be high but learning plateaus.

Research anchors: Vygotsky (1978); Bransford et al. (2000)

Support

Persistence

What support is

Support includes scaffolding and the emotional conditions that allow learners to persist through difficulty. Support does not remove

rigor; it sustains it through feedback, revision, and psychological safety.

Why support matters (mechanism)

Support functions as a persistence constraint. When learners experience challenge without support, effort collapses into avoidance. When support is present,

learners are more willing to take risks, revise thinking, and persist.

Indicators

- Feedback is timely, specific, and usable.

- Revision is expected, not optional.

- Errors are treated as information rather than failure.

- Students seek help without stigma.

Failure modes

- Feedback arrives too late to influence learning.

- Errors are penalized rather than examined.

- Students disengage under difficulty.

- Excessive scaffolding removes cognitive demand.

Research anchors: Black & Wiliam (1998); Darling-Hammond et al. (2020)

Agency

Ownership

What agency is

Agency is the learner’s sense of ownership and influence over learning. Agency is not unlimited choice; it is meaningful participation

within purposeful constraints.

Why agency matters (mechanism)

Agency functions as a motivational constraint. Learners persist and engage more deeply when they experience autonomy, competence, and purpose.

Without agency, clarity and challenge often produce compliance rather than investment.

Indicators

- Students ask substantive questions that shape the learning.

- Learners make meaningful decisions about process or product.

- Curiosity and initiative are visible over time.

- Students take responsibility for improvement.

Failure modes

- Students wait for instructions rather than thinking independently.

- Choice exists only at a superficial level.

- Engagement depends on external rewards.

- Learning feels procedural rather than purposeful.

Research anchors: Deci & Ryan (2000)

Reflection

Transfer

What reflection is

Reflection refers to opportunities for learners to revisit ideas, examine thinking, and connect learning across contexts.

Reflection transforms activity into learning and increases transfer beyond a single task.

Why reflection matters (mechanism)

Reflection functions as a transfer constraint. Without it, learning remains task-bound and short-lived. Learners improve when they analyze errors,

revise work, and articulate understanding.

Indicators

- Learners revise work based on feedback.

- Students explain how their thinking has changed.

- Connections are made across tasks and contexts.

- Prior learning is intentionally revisited.

Failure modes

- The same errors recur across tasks.

- Feedback does not lead to improvement.

- Learning fades quickly after assessment.

- Transfer is rare and accidental.

Research anchors: Bransford et al. (2000)

References

- Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning. Assessment in Education, 5(1), 7-74.

- Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. R. (Eds.). (2000). How People Learn: Brain, Mind, Experience, and School. National Academy Press.

- Darling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Cook-Harvey, C., Barron, B., & Osher, D. (2020). Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Applied Developmental Science, 24(2), 97-140.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The ‘what’ and ‘why’ of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227-268.

- Hattie, J. (2009). Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. Routledge.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Harvard University Press.

You can also find related graphic we created in 2015 below, for a few additional thoughts that aren’t strictly research-based.