Bookshop CEO Andy Hunter is expanding his Amazon fight to ebooks

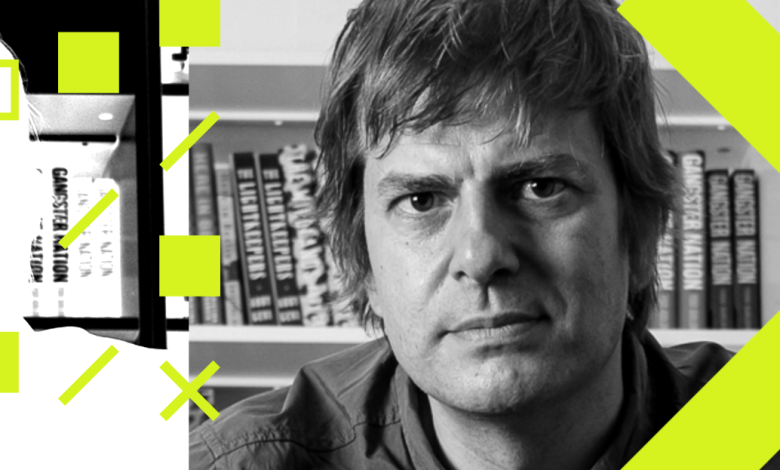

Today, I’m talking with Andy Hunter, the CEO of Bookshop.org. Bookshop, at its core, is a website that lets local bookshops all over the country — and in a few other countries — sell their books online. If you want a book, you go to Bookshop and click buy — it’s just as easy as Amazon, except a local bookstore gets some of the money.

Just recently, Bookshop launched ebooks to compete with Amazon’s giant Kindle business — a simple idea with some fun and complicated Decoder problems just under the surface.

Andy started Bookshop in January 2020 after years of frustration with Amazon. It was a bad time for the world, as covid-19 pandemic lockdowns were about to begin, but it was a great time to launch a website that let people support their local stores without going outside. And so the pandemic propelled Bookshop through some very quick early growth.

Bookshop is a mission-driven company with a strong philosophy, and that growth has paid a lot of money out to bookstores. Right there at the top of Bookshop’s website is a big counter telling you how much money it’s raised for local booksellers. Right now, that number is more than $35 million. So I wanted to know: how does that money work, and how can Andy afford to keep the lights on with so much of Bookshop’s profit going back to local bookstores? And I also wanted to know how he’s making enough money to expand, because that expansion into ebooks is a big one.

Listen to Decoder, a show hosted by The Verge’s Nilay Patel about big ideas — and other problems. Subscribe here!

There are plenty of interesting, alternative e-readers out there — the Kobo has a following, and many folks here at The Verge are fans of the Boox Palma. But the Kindle handily leads the marketplace. And Amazon has a big chokehold not just on the Kindle content, but also on the hardware itself, which really doesn’t read other kinds of books.

So, for Andy and Bookshop to get what they want, they’re probably going to have to gear up for a big fight against Amazon to make sure the Kindle can read their files. That’s absolute pure Decoder bait. You’ve got antitrust, closed app stores, file formats, and DRM — we really got into it. The interesting comparisons in my mind are the antitrust cases Epic Games filed against Apple and Google, and you’ll hear us talk in depth about those.

Andy’s also willing to pick some other fights, as needed. Books, after all, are speech. They’re one of the oldest ways we have of sharing and communicating ideas, and the political environment in the United States right now is very hostile to some ideas. Books that discuss race, gender, and sexuality are being banned across the country, and those bans are ramping up as the Trump administration goes to war against whatever it thinks DEI is, using a pretty self-serving view of “free speech.” As you can imagine, someone like Andy, who fundamentally wants books to thrive, has pretty strong feelings about all of that — ones that go far beyond partisan politics.

One note before we start: you’ll hear Andy say that Bookshop is a B Corp. That’s a special certification from an organization called B Lab, which says a company is structured in specific ways that don’t just benefit shareholders. It’s an interesting idea with a complicated history and even a little controversy in the mix — we’ll link an explainer in the show notes.

Okay, Bookshop.org CEO Andy Hunter. Here we go.

Andy Hunter, you’re the CEO and founder of Bookshop.org. Welcome to Decoder.

Thank you, thanks for having me.

I’m excited to talk to you, there’s a lot going on. Bookshop is five, and you just launched ebooks. It sounds like there’s a brewing fight with Amazon that I’m eager to talk about. Let’s start at the start. Bookshop is five. Tell us what it is, how it works, how you kicked it off.

I was working in the publishing industry for about 15 years. I started some companies, Electric Literature and Literary Hub, and some small presses, Catapult, and worked as publisher for Counterpoint and Soft Skull Press. During this time, I was watching as independent bookstores tried to fight off Amazon, and I watched as about half of the independent bookstores in the country went out of business, as Amazon’s market share grew to about 60 percent of all the books sold. And I knew that to have a future with independent bookstores was going to require some kind of e-commerce solution, so that independent bookstores could sell books online and compete with Amazon for those sales, or else it was just going to be a global extinction event for these stores. But I also knew, as a publisher, how important independent bookstores are to having a diverse culture around reading and books. And so I knew that they were worth saving.

So I launched Bookshop.org in 2020 to allow independent bookstores to easily sell books online and allow people who were buying books online to easily support their local independent bookstore. And right after it launched, the pandemic hit and then suddenly we onboarded millions of customers and millions of bookstores, and it’s been a wild ride ever since.

Bookshop.org is a website. You can go to it, you can browse books. I actually just bought a book today on Bookshop.org. I bought a bunch during the pandemic, like you said, and then I was like, I should go check this out again. You go, and then you’re supporting local bookstores when you actually purchase the book, but you don’t hold the inventory, you’re not shipping, they’re doing all that work. How does that play out?

It’s a funny story, but actually, the kind of lightbulb went off over my head when I was reading an article about Kardashians’ cosmetics where I read that they were a company with only six employees, but they were selling hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of products because they didn’t do any of the fulfillment. They just were running an Instagram channel. And I’m like, oh, I think a books wholesaler could do the same thing for books, because bookstores have really limited inventory and they have very limited credit, and they have very limited staff and tech know-how and all of that. So, the idea that bookstores could ever compete with Amazon that has millions of books in inventory is like, no way.

But there are book wholesalers that do have millions of books in inventory that have the capacity to ship a book directly to a customer. So by partnering with wholesalers, we’re able to do direct-to-consumer sales with a very lean team, and the bookstores can sell hundreds of thousands of books without ever having to touch a book, without ever having to do the customer service, without ever having to worry about returns and damages and all that stuff. So it makes it super easy for them, and it’s really worked great so far.

Tell me how the incentives line up there; I’m very curious about this. So there’s your company, there’s the wholesaler. Why do you need the bookstore in the middle to take a cut?

Because if we weren’t supporting bookstores, nobody would buy from us, really. I mean, the whole reason that we have customers in the first place is because people are like, “You know what? I want to keep my money in my community, I want to support my local bookstore. Jeff Bezos doesn’t need my money, I want to opt out of the Amazon ecosystem.” And so that’s our rationale, and that’s also our mission. We’re a B Corporation and a benefit corporation, so we put our mission above financial gain.

So yeah, we would make a ton more money if we didn’t include the bookstores, but also people would have no reason to shop with us. We give over 80 percent of our profit to independent bookstores. It’s been $35 million, actually — maybe today is going to be $36 million — to local bookstores in the US and $40 million to local bookstores worldwide. So, our whole reason for being is supporting the stores.

So when the bookstore owners decide to come to you and sign up, do they get to negotiate their rate? Do you just tell them, “This is how much you’re going to get, we just need your brand”? What do they have to do and how much, and how do they fight for a better deal?

Well, they don’t have to fight for a better deal because we give them the full profit of all their sales. So, the deal is about as good as it can get without us going out of business. We allow people to onboard, it takes about a half an hour. That was really important during the pandemic because they all went into lockdown and suddenly these thousands of stores were like, “Oh, one day I’ll get around to getting a website.” We’re like, “Oh, we have to start selling online immediately.” So, it only takes about a half an hour for a bookstore to set up on Bookshop and start selling books to their customers, which is really critical to its success. And that’s part of how; making it easy was the only way to make it work.

And every bookstore, if they sell a book directly, they get the entire profit off the book sale. And if we sell a book through an affiliate, like we’ve got affiliate programs with The New York Times, The Atlantic, then we give booksellers a third of the profit, a third of the profit goes to support Bookshop, and a third of the profit goes to the affiliate. And then we’ve got some customers that just dive into Bookshop, buy a book directly without selecting a bookstore to support. In those cases, we split the profit between Bookshop and the profit pool, which goes to all the bookstores, and that’s what kind of pays our bills.

Which of those slices of the pie is the biggest?

It’s actually exactly 50/50. So, direct sales and bookstore and affiliate sales are each 50 percent of the revenue, pretty much consistently since 2021. In the beginning because bookstores were closed, 70 to 80 percent of the sales were bookstore sales, but once they reopened and their customers came back into the stores, that dropped.

Do you see that shifting over time, or is 50/50 pretty stable?

We try to keep it stable. We try to make sure that customers affiliate with bookstores because we have our bottom line that we’re trying to hit, but we don’t want to convert more customers to direct or obfuscate in any way the ability to choose a bookstore, because we’re mission based and we want as much money going to the bookstores as possible. So we’re going to hopefully keep it there.

How do you think about growth in that scenario? We’re going to talk about a new initiative. You launched ebooks, you’ve got to obviously spend money to launch a new thing. But if you’ve got 50 percent of the total revenue going out to bookshops, you’ve got to grow somehow to do new things, right?

You grow by increasing the overall size of the pie, right? If last year, around $25 million was associated with bookstores, and then next year if we can keep… As long as we make enough to pay our bills, the bookstore portion could go up to $50 million or $100 million. There’s so much money that Amazon is making selling books every year, billions, that right now we’re at about 1 percent of Amazon’s market share, and 75 percent of our customers used to shop with Amazon.

So all we have to do is get another 1 percent of Amazon’s customers to switch, and then Bookshop and bookstores are going to both be making twice as much money. So, that’s our plan. Our plan is to go after Amazon customers, especially at this cultural moment where people are like, ‘I’m not comfortable with Bezos kissing Trump’s ring, and I want to be out of that whole ecosystem. I want to keep my money in my local community.’ Then this is a perfect time to switch and start supporting independent local bookstores when you buy your books.

I want to talk about that in depth, but I just want to stay on the basics for a minute. Are you profitable now?

Last year we weren’t, but that’s because we’ve been putting most of our expenses into building out this ebook platform. We were profitable for the first three years, when we have been not profitable for two years, and then we’re projecting a profit this year.

How is Bookshop.org structured? How many people do you have? How are they organized?

We’ve got about 40 people. We have a sales team, a marketing team, a dev team, and an operations team, and a customer service team. And we try to stay really lean. We have over $1 million in revenue for every single employee, and by staying lean, we’re able to accomplish our mission, which is to give the revenue back to the local bookstores.

And then inside of those groups, which one has the most people? Is it engineering, is it onboarding?

It’s engineering. No, sorry, it’s customer service, and then engineering is a little bigger than the rest. Yeah, because we’re trying to create the best possible experience for internet shoppers who are interested in buying books. So, we want to be the best store to buy books online, period, and that means we have to build out our technical infrastructure and we’ve got to really invest in that. So, that’s where our focus is over the next five years. We want, like if you’re going to buy a book online, this is the best place to do it. You feel at home here, you love it, it’s got a lot of personality, which meshes with your personality as a person who loves books, all that. And so that requires a lot of development, a lot of user experience work.

And are you expressed as a website? Is there an app? I’m asking about the app because selling ebooks and digital goods on mobile phones is pretty tricky.

Yeah, we launched the app yesterday, and we do not support purchasing in the app. And the reason for that is publishers say that resellers can get 30 percent margins when you sell an ebook. So the publisher gets 70 percent, you as a retailer get 30 percent. Now, if you sell it on the App Store, Apple says we get 30 percent. So that leaves 30 percent for Apple, 70 percent for the publisher. Now that’s 100 percent, so that leaves 0 percent for the bookstore. So you cannot sell ebooks in the app and make even a penny, it’s impossible. So there’s no choice but to circumvent the App Store purchasing and force customers to go to the website to buy the books, which is unfortunate because customers don’t understand that. They just think, “You built this dumb app and I can’t buy ebooks in it, why not?” So you’ve got to try to explain it to them.

I’d say what would be rational is if you were a reseller of a digital good that you would pay Apple 30 percent of the profit margin. Thirty percent of the margin would be reasonable, but by saying it’s a flat 30 percent whether or not you’re a reseller, it makes no sense because if your margins on the product are 30 percent and they take 30 percent, then it’s suddenly impossible to have an ebook app, which is why Kindle, you can’t buy the ebooks in the app either, why you can’t buy audiobooks on Spotify’s app, all of that.

I want to come to that because it seems like the legal and regulatory piece of the puzzle is an important part of how you might grow. But the reason I asked about that specifically is that those are big decisions, right? Those are existential business questions. Can we put this button in this app? Can we have any kind of business if this button is here, even if the user experience is degraded in some way?

You also had to make other kinds of decisions, to be a B Corp — which has been in fashion and out of fashion and comes back into fashion — to position yourself against Amazon specifically. How do you make decisions? What’s your framework?

Well, I mean, the first is alignment with the mission. So, we’re very close to the booksellers. Everybody at this company got into this because we wanted to build an alternative ecosystem to the Amazon ecosystem, that was kind of controlled by readers, writers, publishers, people who are really invested in book culture. So that we don’t just kind of cede the whole territory of this incredibly culturally important product to a single mega retailer. So, we all want that more than anything.

And so for us, success is building out this network of a sustainable, independent ecosystem for bookselling and book lovers that can’t be controlled by Amazon or any other retailer. That’s number one. So, everything has to be… everything on the roadmap supports that end goal. And we try to follow the best ethical rules that we can as a company, because we know that people are shopping for us for ethical reasons. So we have salary transparency. The B Corp company that certifies companies said that we were in the top 5 percent of all the B Corps, according to our internal policies and also the good we do in the world. So we got their Best for the World designation, which we’re really proud of.

So we basically try to walk the walk in every way. And one reason for that is the booksellers are very vocal and very independent people. And if we strayed from the path and it seemed like a money grab or a bait and switch where we were going to become predatory, the booksellers would freak out immediately. So we have to be very transparent. We’ve got to get this whole community of independent booksellers on board. And it’s very hard to get a group of independent booksellers all aligned to the same project, but now we have 90 percent of the bookstores in the country participating in this project. We never thought we would get to 90 percent, and that’s a testimony of how much buy-in there is, and that buy-in comes from the transparency and how we make decisions and how we govern ourselves.

A couple of years ago, I had James Daunt, who’s the CEO of Barnes and Noble, on the show, and he was making a similar kind of pitch that Barnes and Noble had the scale to go compete with Amazon. And the way that he would do it is he would sort of give indie bookstores access to his scale, his wholesaler relationships. Basically, become like the AWS of bookstores, but for buying and selling books in that way. I don’t know if that’s worked out, it’s worked out for Barnes and Noble, but it sounds like you’ve been able to outcompete them with the indie bookstores, right? They’re not as reliant on the Barnes and Noble distribution system, they’re coming to you to do e-commerce.

I don’t know if that was really a priority for B&N. I think B&N did a good job of doing that with their internal, company-owned stores. But how we won, we went to all the bookseller conferences. There’s regional conferences, there’s national conferences. We put members of the American Booksellers Association on our board of directors. Our board of directors actually is majority independent booksellers. We put in our shareholder agreement, we put that we could never sell to Amazon or any other major US retailer. So the bookstores didn’t have to worry about us becoming big, then becoming reliant on us, and then boom, Amazon buys us, we all get rich and they’re left out in the cold. So there were so many things that we did to prove ourselves, but I think forbidding the sale of the company to Amazon, putting independent booksellers on our board, and really servicing booksellers first is what made the difference.

You talked about that cultural moment that we’re in right now. There’s a lot of pushback against the various billionaires being onstage at Donald Trump’s inauguration, at this perception that in particular Jeff Bezos is kissing the ring, because he owns The Washington Post and he wouldn’t let them endorse Kamala Harris. There’s a lot of that going around. Have you seen an increase in sales that you can attribute to people leaving Amazon?

I know that probably the listeners are all over the political spectrum. I can say that I personally am worried about the Trump administration. And so, it’s weird for me that every time something that I consider bad happens, Bookshop benefits. COVID happened, it was terrible, and Bookshop boomed. As soon as Trump won the election, we saw sales start to go up. And then on Trump’s inauguration day and since, we’ve been up 75 to 100 percent year over year. So, we’ve seen a massive amount of customers who are switching from Amazon to Bookshop for these reasons.

Is that the bookstores doing outbound marketing? Is that you sending messages? Is it just people realizing they don’t want to use Amazon and finding you? Where’s that growth coming from?

It’s almost all word of mouth. The thing about being a direct-to-consumer e-commerce retailer that sends all of your profits somewhere else, is that you don’t have any money for digital marketing. So, our digital marketing budget is 1 percent of our revenue. And even if we tried to put all these ads out, saying, “Support booksellers, not billionaires,” we wouldn’t have the reach. So, we rely on word of mouth. And it’s almost all word of mouth. There are people on Bluesky, people on Threads, people on Twitter who are all saying, “How do I get out of Amazon? What alternatives are there?” And Bookshop.org always comes up in those conversations.

Now, to some extent it’s also bookstores and to some extent it’s also us, so all three of them combined — and affiliates. We’ve got podcasts, newspapers, magazines, literary organizations, and influencers. They’re all Bookshop affiliates, so they let their people know, too. Bookshop’s kind of trick — the way that we got enough customers to compete with Amazon in the first place — was by reaching out to small communities. So, we didn’t try to say, “Okay, we want to have 3 million customers. We’re going to go big.” We were like, “We want to have 3 million customers. We’re going to get 3,000 groups of businesses or organizations that each can bring 1,000 customers.” And that’s how we’ve managed it so far. So, they’re all telling the same story and telling people about us.

I’m curious, you said when bad things happen, you see growth. Obviously, there’s the inauguration. Some of our audience thinks it was great. You’re right, some of our audience thinks it was horrible. Can you see in the books how the mood is?

Are people buying a lot of books about fascism or whatever?

On Tyranny is always a top seller. There are also books like Braiding Sweetgrass that are kind of more like how to live well and how to live with wisdom. I think a lot of people are kind of just, “The world is crazy and I need to find some kind of inner balance, or I need to turn off the world and find a way to live well in this environment.” And then you also have all the escapism. So, there’s a ton of fantasy, romance, and sci-fi being sold, because people just want to opt out and go into a different world.

There’s a big question in America, maybe broadly in the world right now about who distributes what, where the limits of platforms and free speech are. Bookstores traditionally just stay out of it. They sell everything. That’s the idea. Do you feel that pressure as your audience or your customer base gets more politicized to not do kinds of things?

Absolutely. The American Booksellers Association always had a commitment to free expression as part of their mandate. And our mission is to support local independent bookstores. Well, guess what? There are Christian local independent bookstores, and so we’re not going to say no to them. So, we have a very high standard for removing books. We do get pressure all the time and we get pressure from both sides of the equation. There was actually a Wall Street Journal editorial that was angry about us once in the books that we were featuring, but we also get angry comments from people on the far left.

And I think if you are committed to books, you’re committed to discourse, and freedom of ideas, and educating people, and promoting critical thinking that allows them to parse the ideas that are in these books. And so, absolute hate speech or lies is a threshold that we will certainly pull something or something that is stolen or plagiarized. But if it’s civil discourse, we’re going to let people discover for themselves what they think about it.

I always think that’s so interesting, because the book community is old. The norms there have withstood much more pressure in many more kinds of ways over time. And you bring that into the modern world, and platform dynamics, and how people think social platforms should moderate it. It does seem like there’s a real tension there between, “Boy, we’re committed to free expression. Also, people are going to yell at us because these Harry Potter books are front and center.” Does that actually play out for you at your scale? It seems like Amazon is so big they can ignore it. It seems like the local bookstore, you can physically yell at those people, but you’re right in the middle of that scale. How does that play out for you?

I mean, it’s like social media flak and emails, but it has never become a lawsuit or something like that. And we are pretty strong about what we believe, so it doesn’t cause me a ton of stress. I guess it causes me the most stress when it’s somebody who I agree with ideologically, who feels somewhat betrayed by the fact that we maybe are featuring a book or that we accepted an ad for a book that they disagree with. And it doesn’t have to be political. We could have an ad for a book that’s about fitness that somebody finds offensive. And we just have to try to stand our ground, because if booksellers are going to start engaging in deciding what books are okay or not okay for people to read, then we’re really screwed. It’s bad enough that the government’s trying to decide that. We need to be committed to letting people have access to information.

Do you see that coming with the Trump administration? It seems like book bans and public libraries and school libraries are on the table. The next thing that happens is we yell at our local bookstores–

That’s the history. It happened in the ‘80s, it’s going to happen again now.

They tried to pass a bill in Texas that said if you sell a book to a minor, it’s not appropriate. Or if you sell a book to a library and that gets a minor access to it, then you’re responsible and you’re liable. And that would’ve destroyed independent bookselling in Texas. But thankfully, it was overturned by a judge, and so that is no longer a threat. Now, the Trump administration, I think yesterday or the day before, said that there is no such thing as book bans. There’s no book ban epidemic in the country and that it’s a hoax. And what they’re saying is that if you’re in a library and you remove all the books about trans people or gay rights or civil rights, that’s not a book ban. That’s just taking books that shouldn’t be available to 18-year-olds and putting them behind the counter or getting them out of the library, but people can access them some other way.

So, they’re arguing about what the definition of a book ban is. For us, it’s like, if you don’t have access to the book, if you are taking access away from people, it’s censorship and it’s a book ban. And it should not be allowed, even if it’s possible for that person to still be able to get a book somewhere else. And honestly, I think it’s disingenuous, because I think that if they did manage to scrub every book of genderqueer out of the libraries, they would probably go after bookstores next. I don’t think that they want people reading these books in general.

So, I think it’s going to be a fight, but it’s definitely a fight that we’re committed to win. And hopefully, cooler heads prevail, because the thing about banning opposing points of view, it doesn’t usually work out for the people who are trying to ban those points of view. It’s never really a good idea. And then the people who come next can just flip it around and do the same thing to your point of view.

I’m just thinking about the history of this. And I promise you I’ll bring this to ebooks, because everything gets bigger once it’s digital. The problems magnify in certain ways. But just thinking about the history of book bans or putting explicit lyric labels on CDs, the pressure was always on the retailers. In the ‘80s and ‘90s and in the early 2000s, we didn’t want B. Dalton Booksellers to have these books in the mall that kids go to, so we’ll pressure the retailers. We’ll pressure Walmart to not sell certain music, and that means the music is broadly not available. You represent the independent bookstores. If the government comes and pressures the bookstore, the bookstore doesn’t have the resources to fight back. If they come and pressure you, you have a coalition of bookstores, you might have the resources to fight back. Do you see that as part of your role here?

It’s primarily the role of the American Booksellers Association, who we are very closely aligned with.

But you’ve got 90 percent of the bookstores. That’s kind of why I’m asking. The pressure will come to you.

We will fight. If we have to, we will fight. I’d rather not because we don’t have a lot of money. But if we have to, we’ll fight. And I will say that it’s so hypocritical. It’s just such nonsense because every one of these people who are screaming about some kid reading, seriously, Anne Frank. Anne Frank is one of the books that they’re concerned about because she talks about sexuality when she’s 13 years old. And so, they’re concerned about books like Anne Frank’s The Diary of a Young Girl. Meanwhile, the internet is filled with porn and the most screwed up, horrible things available. Any 13-year-old with Google can find the most horrible thing that they can think of in an instant. And they’re all online. They’re either on Discord or 4chan or whatever. They are not going to be corrupted by a book.

If you’re lucky, they’re reading Anne Frank’s The Diary of a Young Girl. You have to be really lucky if your kid wants to read books in the first place. And nobody’s going to have their worldview rocked and corrupted by any of the books that they’re trying to ban. It’s a complete charade. There is so much worse material available to every kid, and they’ve all seen it on the internet every single day. The book ban thing is just… Speaking of a hoax, they say it’s a hoax, because it’s not really happening. I think it’s a farce because the people who are involved are only doing it for political clout, leverage, fundraising. It’s not actually about protecting kids. If they wanted to protect kids from certain disturbing images or points of view, then they would be looking at the World Wide Web.

Let’s talk about taking this project and making it digital. Because one, it does seem like you have the stomach for a fight, even if you don’t want to have the fight. But once you make everything digital, once you allow other people to publish ebooks — which is a huge part of the ebook phenomenon in the background that I want to get to. Once you have distribution, that puts you in a fight with the app stores and their fees, you’re in a lot more fights in a lot of different ways. So, tell me, why even start ebooks? Why open the door to this level of conflict in order to sell a product that Amazon essentially dominates the market for?

Well, I think it starts with readers. One out of every six books sold in the country is an ebook, and I can’t buy it from my local bookstore. I took a trip with my kids to Europe. My kids wanted to read ebooks; they had to buy them through Kindle. Or if you’re very educated, you can find something like Kobo, which is an alternative platform. But basically, there’s no way to buy ebooks from your local bookstore. That in itself doesn’t make sense. Something is like 15 to 20 percent of the market, local bookstores should be part of that. And people that want to support local bookstores should be able to do that when they buy ebooks. So, that is about also taking the corporate control out of ebooks.

If one mega retailer is determining how ebooks are sold, what ebooks get marketed, what ebooks get exposed to readers, how the commerce works, and how the authors are promoted, and that retailer has its own self-interest in mind, that is not good for the whole culture around books. It’s not good for authors, it’s not good for readers, it’s not good for publishers. So, we need to diversify the ebook landscape. And we need to give people who want to support their local bookstores a way that they can buy ebooks and support their local bookstore at the same time. That was so important. And additionally, it’s a new revenue stream for bookstores.

Bookstores are always hanging on by their fingernails. We have more bookstores opening now than we’ve had in the past 15 years, but they were one downturn from disappearing. And so, if we can open up a new revenue stream, if they can get 5 to 10 percent of their revenue from ebooks, that’s going to be a total game changer for them. It’ll make them so much more secure in their communities and help all of their outreach and all their programs that make them so valuable. So, it really accomplishes a lot of positive things all at once. And I think that I have a little moral indignation about the fact that there is a fight, that it shouldn’t be a fight. These should be open systems where every retailer can support the same kind of products, and every device can read the same kind of products the way that music works.

What’s interesting about the music industry is that it got digitized first through Napster, which had no business model, and everyone was stealing everything. Then the iPod, and there was a fight over [digital rights management]. And Steve Jobs famously won the DRM fight with the iPod. And they said, “Just publish MP3s, DRM is never going to work,” and the music labels capitulated.

Then we moved to Spotify and we brought DRM back. Now, everybody has a streaming service that streams DRM music. So it goes. With video, broadly, DRM just won from the beginning. Everything was always DRM from the start. Books could go either way. A book is a PDF. I get a lot of galleys from authors who come on Decoder, and I just get PDFs with watermarks. And I’m like, “Why don’t books just work like this?”

But the publishers obviously want DRM. The Kindle file format is DRM to hell and back, and no one else can even read it. There are other formats, but you’re at the most Decoder question of all: you’re in a format war with a very late ‘90s DRM problem embedded in the heart of it. How do you think about that problem? Is it that we need a new format? Is it that the publishers need to give up on DRM because the people want to pay regardless of the existence of piracy? What is the shape of that conversation in 2025?

I have a slightly more nuanced view. I think that if you go out into the internet, about 80 percent of readers don’t notice or care. And 20 percent of them are adamantly and virulently against DRM. And then publishers, of course, are terrified of the Napster days happening to their industry. They don’t want it to all be piracy because the recording industry saw 80 percent of their revenue disappear when music went digital, and they’ve brought it back now with Spotify and streaming, and so now they’ve recovered. But it was a big blow. Publishers obviously don’t want that to happen.

I think that if there’s a system that allows people to own their books, ebooks, so they’re not leasing them but they actually own them. They don’t have to worry about a device taking them away from them or retailers taking their books away or making changes to their books after they’ve purchased them, which we’ve seen with ebooks. So they should own them, they should have control of the content and they should be portable. They should be able to put them on whatever device they want. I think that there should be a way to do that and still keep authors paid. Because completely removing every restriction and just being like, “Okay, we’re going to release the new Harry Potter book as a PDF and hope that people pay for it.” I think that they would suffer a massive loss of revenue.

And I particularly am concerned about authors even more than I care about publishing companies. Authors should get paid for their work. Artists should get paid for their work. Period. And so there should be a system for artists to be paid for the work of writing books and that needs to be preserved. But DRM was implemented based on Amazon’s designs and publishers working with Amazon to prevent piracy. And that happened in 2005, 2006, 2007. It’s been a long time. There’s new technologies out there. We can find a way to create portable, flexible ebooks that are owned that still make sure that the publishers and authors get paid.

That’s, I guess, my Holy Grail, and that’s not going to happen right away. But in five or 10 years, I would love to have the kind of clout that Steve Jobs had in saying, “This has to end or this has to change.” The thing is, before you get that kind of clout you actually have to have some customers. You have to have some readers so that the market will listen to you.

So what kind of files are you selling today?

They are almost all DRM protected using LCP DRM, which is a new standard, which is a great standard. But that’s because major publishers require it. And then we have a small selection of DRM-free ebooks that people will be able to buy and download and use on whatever device they want. And we’re going to be growing that DRM-free selection so that we end up with hopefully a catalog that is diverse and has maybe half DRM-free and half publisher-supported DRM.

The Kindle model works because Amazon sells the Kindle hardware at a loss or break even maybe, and then they obviously assume that you’re going to buy tons of books because it’s all a closed ecosystem. You don’t have any hardware yet. A lot of people like having hardware. Does your model support you selling cheap hardware?

I think it does. If we go that route, we’re going to do it first through crowdfunding, like an indie alternative to the Kindle where you can support your local bookstore. And we haven’t decided whether we’re going to try that or not. We’re going to make that decision in a few months. But we already know it works on devices like Boox, which is an Android e-reading device that is quite popular and our Android app works great on that. We’re going to work with Kobo to make sure that people who buy ebooks from their local bookstores can read it on Kobo, and we’re going to just try to create as much flexibility as possible.

When we launched, a lot of people wanted us to solve every single problem with ebooks on launch day, but that’s not possible. We’re small. We raised $2 million to do this whole thing. Fable, which is another ebook company, raised $40 million to do this. Scribd has raised $200 million to do ebooks. We are small. We have a hundredth of the resources that our competitors have. In the case of Amazon, we have probably one 10,000th of the resources that they have.

But we do think that we will be able to create the best environment and platform for e-reading. It’s just going to take a few years before we can really do everything we can. And we want people to be able to buy an ebook from their local bookstore and read it on their Kindle, too. But we need Amazon to give us permission, to allow us to say, “Send this to your Kindle,” and have that sync with a user’s Kindle account. Which hopefully they’ll give to us, but it’s going to take time for us to negotiate that.

I want to come to that, because that seems like the big upcoming fight, but let’s just stay with the other readers for a second. Basically in the world there’s the Kobo, which a lot of people like. There’s the Nook, which still exists, the Barnes and Noble Nook. I don’t know if that is very popular on your radar, but it’s out there and exists. And then there is the Boox Palma and the ecosystem of basically Android devices with E Ink screens. The Verge team loves the Boox Palma. We talk about this bizarre little thing all the time.

There’s a difference there. The Boox Palma and that ecosystem, they’re Android devices. You can put your app on there and that’s the support. That’s all the more help you need from them. They’re running the Google Play Store, your app’s in the store, you can support your own DRM standard, you can do whatever you want to do. The Kobos of the world are less like that. They’re more integrated in some way. You’ve got to work directly with them to support your standard and your DRM.

That might implicate their business model because they’re probably planning on purchases on their device. How do those negotiations look?

Well, with Boox it’s pretty simple. I send them emails all the time, and they never write me back.

Because your app is just in the store, right?

To whatever extent mobile devices are open, they’re open. But with Kobo, they’re closed.

Yeah. So Boox, it works on Boox. I love it. I wish I could talk to them because I think that we could work together more. And so if anybody from Boox listens to this podcast, write me back. But for Kobo, they want to support us and we want to support Kobo readers. So we will build a tool to be able to send, to buy an ebook from your local bookstore and read it on your Kobo.

Now, there is a danger to Bookshop in that Kobo also sells ebooks. And so if people are buying Kobos because they want to read Bookshop ebooks, they could switch and just out of laziness or lack of knowledge, just end up buying ebooks from Kobo, and that wouldn’t be great. But we try to enter into these agreements with good faith. And I think that the Kobo team has a lot of respect. I know that their CEO has a great reputation. So I’m thinking if our customers want it and Kobo wants to support it, we’re going to trust them to not try to steal up all our customers and we’re going to support Kobo.

Do they have to do anything special to support your DRM or your file format?

Yeah, I think they will. Not a huge engineering lift, but they’ll have to spend a few weeks on integration.

And then when I think about other platforms that are sort of similar, Roku comes to mind, right? Roku is pretty open, they’ll take any app that wants to play, but then they take a cut of the advertising that appears across all the apps. And sometimes we hear about some friction in those relationships. Does Kobo ask for a cut of your revenue to appear on their service to do that work?

They have not yet, no. I think that they will, I imagine that they just want to sell more and that’s their motivation.

So that’s the alignment, right? And I kind of want to drill on this a little bit, too. You guys are aligned because you want to take market share away from Amazon.

So you’d like to just sell some books that Amazon isn’t selling. That’s pretty zero-sum. I think Kobo would like to say, “Our device is more flexible than the Kindle. Look at this huge list of supported partners.” It feels like whatever you learn from Kobo is not going to be applicable to the fight you have with Amazon.

No, it’s not going to really be the same.

Let’s talk about Amazon then. I can see the broader ecosystem. There’s an argument that you should just let Amazon and the Kindle be whatever it is, and you should draw people away to this alternative ecosystem and say, “Look at how bad that is. It’s locked you in. Look at how open the world of the Kobo and the Boox Palma is.” I have not one but two e-readers. Innovation is happening here. And then there’s the argument that says you should just go fight Amazon and say, “Let me sell books on your hardware.” It seems like you’re going to go pick the fight. Why are you picking the fight?

Well, unfortunately, I spent the past five years bad-mouthing Amazon, so asking nicely probably won’t work. But I will say the first thing we’re going to do is ask nicely because it doesn’t make sense for you to have to buy an ebook from Amazon in order to read it on your Kindle. And we know that they did an integration with Libby to allow people who take out library books to read them on their Kindle. So we know it’s possible. We know that it took a couple of years for Amazon to agree to it and to facilitate it, so this isn’t going to be a quick fight.

But I think our first tack is going to be to go to Amazon and say, “Hey, independent bookstores are in trouble. A lot of independent bookstore customers have Kindles. They want to use them. They want to buy their ebooks from local bookstores. Be the better company. Do the right thing. Let people read these on their Kindles.” If Amazon says yes, then we’re going to announce that people can read ebooks on their Kindle they bought from the local bookstores, then we’re done.

If Amazon says no, then it’s an antitrust issue because you can’t have a device that has 85 percent of the market for e-readers and say, “Actually, you’ve got to buy everything on this device. You’ve got to buy it from us.” That’s equivalent to if Apple said on the iPhone, you can only buy music from Apple Music. You’re not allowed to have Spotify or any other platform title, whatever. No other music is allowed on the iPhone. You have to buy it from Apple Music because of piracy. And you also can’t watch Netflix on your iPad anymore. No, you’ve got to go through Apple TV and you have to download all of your movies from Apple TV as well because we’re worried about piracy, so we can’t allow Hulu or Netflix or whatever. Obviously, nobody would stand for that. It would be insane.

Back in the ‘80s when Microsoft was selling every copy of Windows and they were like, “You have to use Microsoft Internet Explorer,” that was an antitrust issue, too. And Netscape successfully sued them, and Microsoft had to open it up. When you have complete control of a market and you’re shutting out all of these content sellers based on your ownership of the hardware, you have an antitrust risk. And so I think that we have a strong case that as a hardware manufacturer, they have a very popular piece of hardware. That’s great. They can’t control where people buy things in order to use it on the hardware.

I hate to be pedantic, but I feel like the CEO of a bookstore company is the right person to be pedantic with. The Justice Department sued Microsoft and tried to break them up. That started with Clinton, went to Bush, and they eventually settled. Microsoft didn’t win or lose, they just ended up under a consent decree that Microsoft will tell you distracted them for years and allowed Netscape and whoever else to thrive. It’s much more complicated than Netscape, but that’s the shape of it.

That’s also the shape of a lot of things that are happening now in the antitrust world. Google is being sued and the government would like to break off Chrome from Google. That rhymes with the Microsoft case. Apple is being sued by the Justice Department and we’ll see how that goes. Epic Games famously has sued Apple and Google. That feels like the most direct comparison to what you’re saying about Amazon. Epic sued Google. They won because Google has to pressure its partners, it has to pressure Samsung and Motorola and whoever else, to keep control of the phones when they run Android. And so there’s a lot of deal making and contracts and evidence that Google exerts this pressure on its partners. And so Epic won because they were able to show that pressure.

They more or less lost against Apple because Apple doesn’t have to exert pressure on anyone. They don’t have to behave anticompetitively when it’s their own phone in their own store. And that’s what you’re up against here with the Kindle, right? It’s Amazon’s device, it’s their store. They have the Apple precedent that’s going to say, “Well, you own the whole thing, tip to tail. You’re not doing anything anticompetitively because there’s no one else in the mix.” And you’re going to have to show, “Well, this is harming consumers. It’s raising prices.” How are you thinking about that fight given that context?

Apple has Android to point to saying, “We don’t control this market.” So the phone market is very diverse compared to the e-reader, E Ink device market where Amazon has a very, very locked down control of it. And all books and Kobo are just tiny fractions of the market compared to Amazon’s control. So I think that there’s a much stronger argument that there isn’t another place to go.

If you’re an independent bookstore and you want to sell books, ebooks to your customer, they’ve almost all got Kindles and asking them to buy a different device is onerous. How is it harming consumers? I think that that argument will have to be more like how is this harming small businesses? It definitely harms small businesses because it makes it impossible for them to sell ebooks to their customers. And the more that you have market control, definitely in terms of discounts, daily deals, sales, that kind of thing, independent bookstores can’t create their own ecosystem.

So maybe an author would be like, “Okay, I love my local bookstores, so I’m going to do a special deal where for my local bookstores they can sell my ebook for $1.99 for the next six weeks.” They can’t do that right now because of Amazon’s control of the market. So if we have a more diverse market, then there’s competition between them and then possibly consumers will benefit.

I’ve asked a handful of questions about Epic. They’ve been at the vanguard of fighting the App Store, antitrust fights. Have you talked to [Epic CEO] Tim Sweeney? Does he have any tips for you?

No, I would love to, but I think Bookshop is just becoming big enough that we would be on people like that’s radar. We were an underdog with almost no funding and we didn’t exist five years ago. And now we’re becoming big enough that people are noticing us, and so I’m hoping to have those kinds of conversations now.

The other antitrust case that I think about in this context is actually a books case. The Justice Department, I believe, sued Apple because it wanted to create new kinds of contracts to compete with Amazon, to put books on the iPad at the beginning. There were some very complicated dynamics around pricing and who would get to price what and how, and most favored nation trading agreements. And in the end, Apple lost and it feels like they also stopped caring about books at all. They’re not a competitor. We have barely even mentioned them in this context. And Amazon still dominates the marketplace. Have you looked to that case at all? Is there anything to learn from that? Because I think most people would tell you that one was a failure. It didn’t achieve its goals, even though they won.

I don’t know what the Justice Department was thinking, but that was a big priority for them and it was a big gift to Amazon. I mean, what I learned from that is be very, very careful not to collude with anybody. Be very careful talking about discounts, talking about strategic plans with publisher partners, et cetera. So we don’t do that. I mean, I’m very open about what our ambitions are.

I’ll talk on a podcast about them, but I don’t go into any back rooms because I think that’s what really screwed over Apple and the publishers, is that they were kind of plotting “how do we arrest the ebook market from Amazon and create a more diverse ecosystem like Bookshop?” It’s like we’re trying to do the same thing. We want to create a diverse ecosystem around ebooks, too, but we’re not like smoking cigars in the back room of Penguin Random House trying to figure out how to do it. We were just openly operating and trying to just negotiate contracts with people and work within existing frameworks.

I will say the only thing I truly remember about the Apple ebooks case was that there was some evidence that there were back rooms and Eddy Cue was in the back rooms drinking wine and making deals. And to me as a baby reporter, my eyes are open, I was like, “There are back rooms?”

It’s very good. Isn’t Apple the bigger problem here or Google the bigger problem here, that you can’t just straightforwardly sell digital products in your app? Wouldn’t that let you compete against the Kindle much more than just head up fighting Amazon?

It would, and that’s another big part of it. So as I think I said in the beginning of the podcast, if Apple wants this 30 percent, that’s fine. But it should be 30 percent of the available profit margin, not 30 percent of the cover price because the cover price does not reflect what the profit is for us as a retailer. And if Apple was like, “We’re going to take 30 percent of all of your book sales after you pay the publishers,” we would be selling tons of ebooks on Apple. And maybe that’s a rational perspective and we could get them to do it. I think that the reason that they wouldn’t do it is not because it doesn’t make sense. I think they wouldn’t do it because they don’t want to lose any leverage. They’re trying to stand very firmly against things like gaming companies, et cetera.

And so to make anything that would look like a concession, even if it made sense, I don’t know if they would do it, but we’ll try for sure, because we don’t want customers to have to jump through hoops. Literally, I had an employee’s mom try to buy an ebook yesterday and be like, “Oh, I don’t understand this app. I’m very excited about you guys doing this, but I can’t buy an ebook. I can only add it to a digital wish list.” And she just thinks we’re bad at our jobs. She doesn’t understand, no, there’s actually an economic reason for this.

It’ll benefit consumers, it’ll benefit everybody if the app stores change, but also it’s really important for E Ink devices to change because most people who read ebooks, they want to read it on an E Ink device, and Kindle is by far the most popular. So, I’m glad that books exist. I have also reached out to reMarkable. I’ve been reaching out to all these E Ink companies, none of them write me back. It’s very sad. But one day they will. Maybe now that we’ve been in The New York Times about this and now that I’m on this podcast, they’ll start writing me back and we can really start pushing their products because we have over 3 million customers. We have over 2,200 retail locations. There’s a lot of opportunity for other E Ink companies to go in and use e-reading as a way in to become a much more popular device. And so I’m looking for people to partner with on that.

The underlying user experience that makes all this work is really just about seamlessness. Right? You buy one of those devices and maybe you bought some books from Bookshop, and maybe you bought some books from the native Kobo experience, and maybe you’ve bought some Kindle books. You’re kind of right. I keep making the comparison of Roku, but you’re kind of right where people are with streaming video now, which is, I have a million different pieces of content across a million services and no one has built a UI that harmonizes it all.

It’s even weirder with books because it’s just text files. It’s crazy that the DRM can silo text files in that way. Is there any push to letting other apps read the files you’re selling or alternatively letting your app read the Kindle files? Because that’s what you really want, is a unified library.

I would love it. I think all digital content should be portable, and I’m not a big blockchain person. I think a lot of it has been hype and smoke and mirrors, but blockchain makes sense for me in that regard. There should be some kind of portable ownership of digital goods that is verifiable, that can control piracy but also allows people to say, “This is my ebook. This is my movie. I’m getting a new device. I’m switching from Apple to Samsung or whatever. I’m going to take my library with me.” That’s basic, everybody would agree with that. So it’s going to take a long time for that to happen, but I think in the next five or 10 years, it’s possible.

I feel like I can hear Decoder listeners with Kindles. They’ve been yelling at us the whole time because the send to Kindle button exists for EPUB files or whatever. It’s been there for a minute. Is that an acceptable add? Is that something you can let people just do from the Bookshop app?

We can do it for DRM-free titles. Now of the major US publishers, there’s only one imprint that supports DRM, which is Tor, which is a great science fiction publisher. I love them. And Tor books would be possible, and any publisher or author, indie authors especially that don’t require DRM, you could use that for it. But there is no way to buy a DRM encrypted book, which means there’s no way to buy a book from Penguin Random House, the largest book publisher in the country, and read it on your Kindle without buying it from Amazon. So if you want to read almost any book on The New York Times bestseller list on your Kindle, you have to buy it from Amazon right now because those publishers require encryption.

Changing that whole landscape either by giving Amazon permission or whether Amazon giving us permission or enabling sideloading somehow or “send to Kindle,” I’d say that that’s phase two. Phase three is looking at the whole way that ebooks are sold and owned and transcending the kind of leasing model where people don’t actually own ebooks, they’re all on lease. And figuring out a better way to do it where consumers can buy ebooks and have a library that’s portable and that they can own for 100 years, that they can give to their grandkids.

When you think about that, that’s like a user experience. Does the technology to do that exist today outside of maybe some blockchain hype?

Yeah, not really, no. That’s why I’m saying a 10-year horizon on it.

There’s the 10-year horizon and then there’s just the reality of today. And I kind of want to end here because it’s more or less where we started. The Biden administration, the Lina Khan FTC, were probably broadly supportive of these ideas. Right?

I haven’t asked any of them, but, “We should make things more interoperable and the big companies should be smaller,” broadly speaking, that was what the Biden administration thought. The Trump administration is like, “Do more mergers. We’re getting rid of our antitrust enforcement.” How do you see all these fights playing out now that the landscape has shifted so dramatically?

I think it’s really dangerous, and I think that people mistakenly think that, “Oh, this is capitalism,” but it’s really monopolism. So capitalism and the free market can be fine, but if you try to allow companies to become monopolies and let them control the market so they can ensure profitability and stifle competition, that’s no longer what’s good about capitalism. And so while the Trump administration might pretend that they’re unleashing business, what they’re really doing is just allowing for more consolidation and more control.

And if you have other control, like if Musk buys TikTok, which they’re floating, then you’ve got one person in charge of two major social media companies that then creates more possibilities of bias, and it seems like there’s going to be very little antitrust enforcement under this administration. And then you look at what happened just now with OpenAI and the Chinese AI company, and you see what can happen to markets that are so reliant on capital that they have this great consolidation. They can actually get disrupted in the end by a free market that is much more loose and distributed. So I think the Trump administration and the big business people that think that they’re going to hit the jackpot by removing all regulation are in for a rude awakening because they’re not going to be helping themselves in the end. Unless they can reach complete control, in which case we’re all screwed, they’re going to end up being too big to fail and then being disrupted and failing.

Let me just bring that back to the specifics of, “We’ve launched ebooks and there’s a fight against Apple to let you sell ebooks on your app and a fight against Amazon to let you read ebooks on their device.” Even just in the past six weeks, the dynamics of the regulatory environment that would let you win or lose those fights have changed. Has it changed your appetite for those fights?

No, not at all. Time goes on. All those fights would take five years anyway. That’s why diplomacy is our first option. I’m going to try to reach these through diplomacy, and I’m also going to try to build really robust alternative systems that will make this less important. So we do a lot of different things at once, and then some of them will succeed and some of them will go nowhere. But the ultimate goal is we’re going to have the best ecosystem and reading experience for people who buy ebooks, and we’re going to use that platform to support local businesses, keep money in people’s communities, support the kind of activism and endorsement of books and literary culture that small bookstores perform every day in their communities.

And so it’s all going to be good, and it’s not going to be owned by a giant monopolist. So that’s going to be good, too. And it’s going to preserve book culture. And I personally feel like my life would’ve been totally empty without books. I really am one of these people who say books changed my life or saved my life. And so giving back to that, preserving that culture, making sure that it’s sustainable and thrives in the next 10, 20, 30 years is completely worth the fight.

I can’t think of a better place to end it. Andy, thank you so much for joining Decoder.

Decoder with Nilay Patel

A podcast from The Verge about big ideas and other problems.