Do You Want a Job Because You Are Black or the Best?

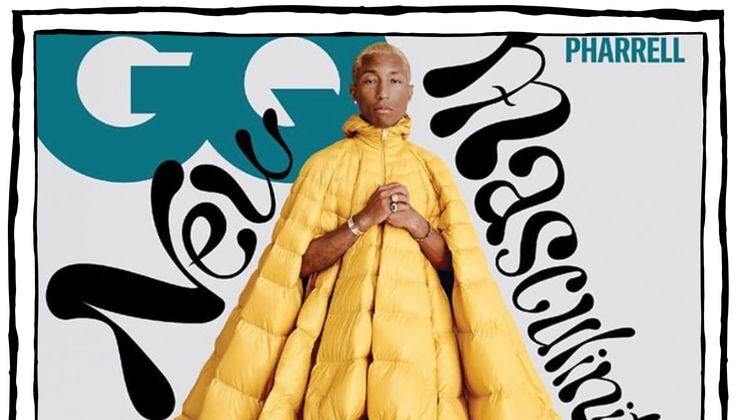

At Miami’s 5th Annual Black Ambition Demo Day, Grammy‑winner Pharrell Williams accepted the city’s key from Mayor Daniela Levine Cava and turned the celebration into a provocation. In front of investors, founders and a surprise performance by Chance the Rapper, he asked:

“Do you want the job because you’re Black or because you’re the best?”

He then dismissed partisan politics, calling it “a magic trick that isn’t real,” and added:

“Supporting a business shouldn’t be based on someone’s skin color—it should be based on the pieces that are the best.”

The remarks instantly lit up X. User @Marcel4Congress replied:

“Pharrell and many others apparently are ignorant as to how anti‑Black American hatred works. For centuries, we were locked out and denied opportunities even when we WERE the best. This legacy still continues now.”

Marcel expanded, echoing Williams’s own phrasing and insisting that “special treatment based on skin color” is a mistake. The tweet captured a growing split: some applaud the call for a merit‑first hiring model, while others argue that it ignores the structural barriers that have long kept Black talent out of the “best” pool.

A recent working paper titled “A Discrimination Report Card” (University of California, Berkeley and University of Chicago) provides hard data to the debate. Researchers filed 83,000 fictitious applications for 11,000 entry‑level positions at 97 Fortune‑500 firms. The study found that employers called back applicants with white‑sounding names about 9 % more than those with Black‑sounding names on average, and the gap swelled to ≈ 24 % at the worst‑performing companies. Names such as Brad and Greg were contacted far more often than Darnell and Lamar, echoing the classic 2004 audit that first documented a 50 % callback advantage for white‑coded resumes.

Pat Kline, a Berkeley economics professor who co‑authored the paper, explained the motivation:

“Putting the names out there in the public domain is to move away from a lot of the performative allyship… We’re trying to create kind of an objective ground truth here.”

The report also showed that bias varied by industry. Auto‑parts dealers and used‑car retailers scored the worst, while firms with centralized HR processes—Charter/Spectrum, Dr. Pepper, Kroger and Avis‑Budget—had the smallest “contact gap.” Heather Ross, vice president of strategic communications at Genuine Parts Company, responded to the findings:

“We are always evaluating our practices to ensure inclusivity and break down barriers, and we will continue to do so.”

Career coach Dorianne St Fleur, who works with women of color, warned that the problem extends beyond entry‑level roles:

“I’ve seen it throughout the organization all the way up into the C‑suite.”

Williams’s current push for a purely merit‑based hiring ethos revives an earlier, more controversial statement. In a 2014 interview with Oprah Winfrey, the multimillion‑dollar musician coined the phrase “The New Black.” He told the billionaire host:

“The New Black doesn’t blame other races for our issues… It’s a mentality and it’s either going to work for you or it’s going to work against you.”

Writer Feminista Jones responded with the hashtag #whatkindofblackareyou?, arguing that a single celebrity’s definition of Blackness “is a slap in the face” to the community’s diverse experiences. Jones wrote:

“Acting like there is any one way to be Black is as problematic as acting like Blackness can be redefined because one celebrity says it is.”

The juxtaposition of Williams’s “New Black” philosophy with his recent hiring question underscores a tension that runs through the data: merit matters, but the pool from which merit is drawn is still uneven.

While sparking debate in the United States, Williams has also been active on the international philanthropic stage. In November 2018 he performed at the Friends of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) Western Region Gala in Beverly Hills, where the event raised a record $60 million for Israeli soldiers and their families. In his brief remarks, Williams condemned the recent Pittsburgh synagogue shooting, calling it “incredibly cruel” and praising the resilience of the Jewish community. He closed the evening with a performance of “Happy,” noting:

“This song reminds us of something you can use when you’re down, when things are discouraging… So, let’s celebrate right now. Let’s be happy.”

His involvement in the IDF fundraiser demonstrates that, beyond domestic debates about hiring, Williams leverages his platform to mobilize large sums for causes he deems important, even when those causes sit at the intersection of politics and identity.

The conversation now circles back to a fundamental question: should hiring decisions be framed solely around perceived competence, or must they also confront the lingering structural barriers that keep Black applicants from ever being considered “the best”? Pharrell’s remarks have forced the debate into the public arena, and the answer will shape how corporations, investors and policymakers pursue equity and excellence in the years ahead.