Remembering the 1972 National Black Political Convention: 15 Things to Know

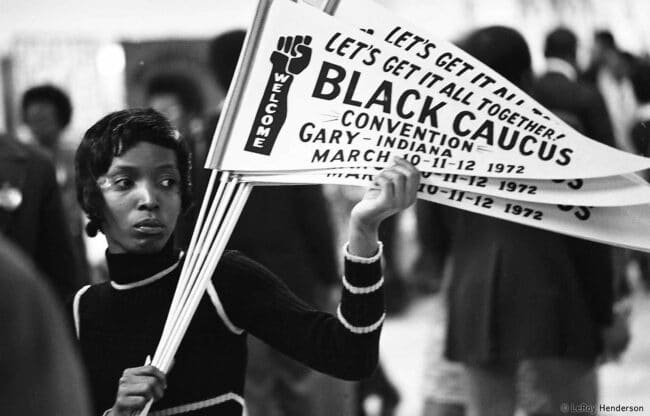

Fifty years later, the 1972 National Black Political Convention in Gary, Indiana, still stands as one of the most ambitious experiments in collective Black politics in U.S. history. It was a moment when thousands gathered under the banner “Unity Without Uniformity,” attempting to define what independent Black political power might look like in a country emerging from the Civil Rights and Black Power eras.

The Convention’s energy was electric, but its legacy remains contested. Was Gary a turning point, a lost opportunity, or the beginning of modern Black political identity? Here are 15 things to know about the Convention — its triumphs, contradictions, and enduring lessons.

1. Gary, Indiana, was both a symbol and a statement.

Gary, a majority-Black industrial city led by Mayor Richard Hatcher, embodied both the promise and the peril of Black urban America. Hosting the convention there signaled that Black political independence would begin in the communities most impacted by racism, unemployment, and economic decline.

2. Over 8,000 delegates and observers gathered in a historic show of unity.

Civil rights veterans, elected officials, Black nationalists, feminists, trade unionists, and artists filled the West Side High School auditorium. Delegates included Amiri Baraka, Jesse Jackson, Coretta Scott King, Betty Shabazz, and Muhammad Ali. The mixture of church revival, political summit, and cultural festival reflected the fullness of Black America.

3. “Unity Without Uniformity” was the rallying cry — and the core dilemma.

The Convention aimed to unite diverse strands of Black politics, but ideological divisions soon surfaced. As Paul Prescod notes, “racial unity was not enough to overcome the vast differences in ideology and class position that existed within black communities.” Gary’s greatest strength — diversity — was also its deepest fault line.

4. The Gary Declaration captured the movement’s spirit.

Its opening line was thunderous: “While the white nation hovers on the brink of chaos… we stand on the edge of history.” The document demanded that Black people stop relying on the “decadent white politics of American life” and organize independently. It was part manifesto, part warning — and it remains one of the most radical collective statements in Black political history.

5. The call for an independent Black political party divided delegates.

Baraka and others pushed for full political independence; Hatcher and members of the Congressional Black Caucus urged continued — though critical — engagement with the Democratic Party. The compromise kept the convention united, but it diluted the radical edge that had initially inspired it.

6. Shirley Chisholm’s 1972 presidential campaign was a lightning rod.

Chisholm’s run embodied both progress and contradiction — a Black woman seeking the presidency through a party many delegates saw as irredeemably racist. Her campaign symbolized the limits of representation within an unchanged system.

7. The class divide within Black America was undeniable.

Many observers — including William Strickland and later Prescod — noted that Gary reflected the aspirations of a growing Black middle and political class, not necessarily the Black working class. Strickland called it a “petty bourgeois” gathering that ignored its own class contradictions.

8. The convention’s agenda mixed reform and revolution.

The National Black Political Agenda combined calls for universal healthcare, higher minimum wages, progressive taxation, and an end to the Vietnam War with nationalist proposals for community control, a Black development bank, and separate labor institutions. As political scientist Robert C. Smith observed, it was “internally contradictory, blending elements of reform and revolution.”

9. Internal disunity foreshadowed the convention’s decline.

Tensions flared — from Charles Diggs’s procedural missteps to Coleman Young’s Michigan delegation walkout. These moments previewed what would follow: ideological fragmentation, organizational drift, and the inability to build a durable, mass-based movement.

10. The media and the Black press offered mixed reviews.

While many attendees called Gary a success simply because “We met, therefore we won,” others were harsher. The Chicago Defender dismissed it as “a babel of ideologies.” The divide between celebration and critique mirrored the convention’s internal split — between symbolic unity and material strategy.

11. “Unity without uniformity” gave way to political reality.

Mayor Hatcher later admitted: “You can be very Black and very unified in Gary… but when you get back home, your political future depends on how well you fit into the very white regional machine.” The local realities of patronage, funding, and governance limited what delegates could achieve.

12. The convention’s follow-up efforts lost steam.

Subsequent meetings in Little Rock (1974), Cincinnati (1976), and New Orleans (1980) failed to replicate Gary’s energy. The proposed National Black Independent Political Party (NIBPP) never developed a true mass base, becoming, as historian Cedric Johnson put it, “a politics of meetings rather than mobilization.”

13. Critics like Harold Cruse saw Gary as both achievement and epitaph.

Cruse called the 1974 follow-up a “betrayal of the Black militant potential built up during the Sixties.” Yet he also recognized Gary as a pivotal moment — the end of the Civil Rights–Black Power continuum and the beginning of a new, more institutional era in Black politics.

14. The spirit of Gary lived on in Jesse Jackson and Barack Obama.

Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition campaigns in 1984 and 1988 revived Gary’s multiracial progressive vision. Obama’s 2008 election, while different in tone, built on the political infrastructure Gary helped inspire. Each represented a new chapter in the long arc of Black political aspiration.

15. Gary’s lesson: unity must be built on shared material struggle.

Prescod reminds us that nostalgia alone cannot substitute for a mass base. The convention’s failure to address class divides foreshadowed today’s dilemmas — a large Black political class coexisting with widening inequality. True unity, he argues, must emerge from collective working-class power, not symbolic gatherings.

Legacy: Still Standing at the Crossroads

In 1972, the Gary Declaration warned: “We stand on the edge of history and are faced with an amazing and frightening choice.” That choice — between symbolic inclusion and structural transformation — still defines Black politics today.

Gary was both a beginning and an ending: a grand attempt to fuse the moral power of the Civil Rights Movement with the militancy of Black Power. Fifty years later, it remains a reminder that political liberation demands not only unity of color — but unity of purpose, class, and vision.