What Does The Fashion Industry Owe To Black Stripper Culture? – Essence

There’s no denying the impact of Black culture on mainstream fashion. This we know. This, we have think-pieced, essayed, and beaten until the horse was bloodied. We’ve drilled down cultural appropriation to a hollow accusation, traced every borrowed trend back to its Black roots, and rabbit-holed our way through history, digging as deep as the discourse would take us. Or have we? The thing is, if we really want to talk about the trickle up fashion theory, we’d have to start by going underground.

To many outsiders, strip clubs have long been seen as spaces for degenerates, aimless men, and wayward women—glittering voids that swallow lost souls rather than hubs for the empowered and entrepreneurial. But no matter what led them to those doors, whether survival, ambition, or something in between, Black dancers were often turned away as strip clubs modernized in the 1970s, told that patrons wouldn’t respond positively to dark or ethnic skin. This exclusion forced them to perform elsewhere, giving rise to new, Black-owned venues, primarily across the U.S. South, and the birth of a new pole aesthetic.

Depending on location, white strip clubs’ aesthetics in the 1980s and early 1990s leaned into a rock-and-country-adjacent, Playboy Bunny meets glam metal look: big teased hair, daisy dukes and a few rhinestones for dazzle. Black strip club dancers, however, adopted a different approach, one that left behind any trace of a girl-next-door fantasy and embraced a brand new flex.

Neutral and pastel palettes gave way to bright neon colors that made brown hues glow under stage lights. Mesh and crochet designs replaced simple fabrics, and monogrammed lingerie elevated the vibe for both performers and club patrons. These women weren’t just talented dancers, they were aspirational. And for top dancers, custom looks were a standard.

Former dancer and Miami club legend Janie Howard, known by many as Pinkey, recalls paying over $200 for custom two-piece outfits in the mid-1990s, with specially selected fabrics and hand-sewn embellishments, a trend that quickly spilled out of the clubs and onto the streets.

“I would even get my shoes custom-designed to match. Everybody couldn’t do that, of course, but the top women could,” Howard tells me over a phone call. “You had to look like money to make money.” As a fan favorite from Club Rolex to Coco’s, she had the respect and the revenue to create a lane entirely her own.

While some of the girls dressed down in designer clothes, others were donning furs in the club. In 2024, Khloe Kardashian was photographed in a fur coat and hat draped over a Gucci bikini, styling that fashion media dubbed the “mob wife” aesthetic. Yet, it partly originated in Black strip clubs. Over twenty years prior, the late DJ Kay Slay was known for hosting fur coat contests at the Bronx club The Golden Lady. Kay would pass out minks and other variations, and the ladies would style them with little to nothing underneath. But this is hardly where the ties between hip-hop fashion and Black strip clubs end.

It’s well-documented that the strip club moved the needle on what was considered hot in the music scene. Artists, producers, and DJs from the era will tell you—if it didn’t move the dancers, it was a definite flop. Beyond this, the styling of the performers would inspire industry professionals (mostly men) to weave Black stripper aesthetics into their productions.

Before the adoption of Black stripper aesthetics across hip-hop, women in the rap game often leaned into baggy, oversized clothing to command respect in a male-dominated space. Popularized in the 1990s by artists like MC Lyte, Queen Latifah, and even R&B groups like Xscape and TLC, this look subverted expectations of hyper-femininity and deflected the male gaze. But as strip clubs gained mainstream popularity and celebrity appeal, even becoming meeting grounds for industry professionals, their influence extended beyond the club. It was then that styling choices for female artists began to shift, influenced by the men working to shape their public images.

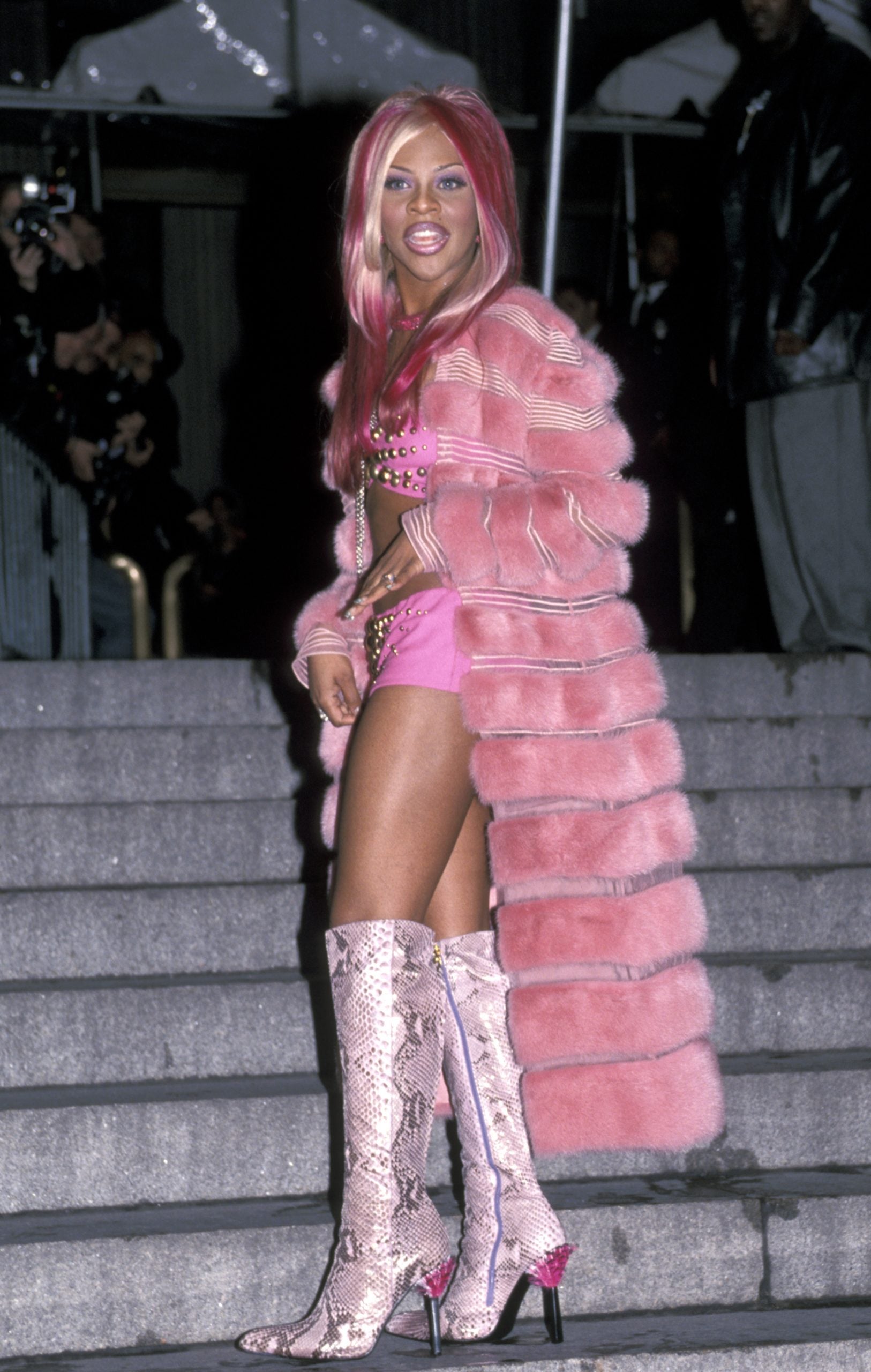

Take the lauded image of New York rapper and artist Lil’ Kim—a young beauty and high-powered lyricist originally from Bedford-Stuyvesant who reached for her dreams of superstardom alongside Notorious B.I.G. and the entire Bad Boy family in the early 1990s. With the guidance and style prowess of stylist and designer Misa Hylton, the artist confidently stepped into a rap world that initially had little room for women embracing overt sexuality.

Her signature style, which included custom-made pasties, mink coats draped over lingerie, and monogrammed bikinis, was both high femme and intentionally theatrical, transforming the 4’11” artist into a larger-than-life figure. In an industry unaccustomed to female rappers crafting fully realized visual identities alongside their lyrical prowess, Kim’s aesthetic, much like that of pole performers who command attention through costume and presence—was as much about visual storytelling as it was about fashion.

With her look, Kim stood at the forefront of a major shift in styling for Black women artists of the time. This move didn’t just redefine her as an artist; it also highlighted how Black stripper culture was being adopted and reshaped in mainstream music and fashion, signaling a cultural turning point in how Black women artists were styled and viewed. Hylton has expressed how she pulled from her background to create the artist’s ensembles. The looks created a blueprint that countless stylists are still following today.

Films like The Players Club, directed by actor and rapper Ice Cube, brought the world of Black strip clubs further into the public eye, reinforcing their cultural impact. What was once workwear for dancers could now be seen on celebrities, fashion models, and concert-goers. The boundary between what was once considered club attire and mainstream fashion began to blur, with Black stripper aesthetics moving beyond the velvet ropes and onto the red carpet.

While Lil’ Kim embodied a self-possessed woman who deliberately embraced hyper-sexual fashion—gracing album covers and magazine spreads as a symbol of empowerment for some—she was also met with harsh criticism. Yet, as she took the heat for pushing boundaries, other women in the shadows of the music industry faced even more severe backlash. Dismissed and ridiculed for dancing suggestively in the background roles they played, they were often seen as mere accessories to male success, despite their essential role in hip-hop’s most visually ambitious projects: music videos.

Few people know that before there were glammed and glossy “video vixens,” women were being plucked from poles across Atlanta, Houston, Miami, and other major southern cities to dance behind male leads. Pinkey recalls meeting rapper and former lead of the 2 Live Crew, Uncle Luke, while still in high school, when he was actively recruiting Miami club dancers for his music videos. Insisting she was too young to join at the time, he later gave her a spot in the 1994 track “It’s Your Birthday,” where she earned both a shoutout in the lyrics and a cameo on screen.

Throughout the years and into the bling era, video vixens took center stage in increasingly polished productions, such as Jay-Z’s single “Excuse Me Miss.” As casting agents began opting for models and actresses as the “main girls,” phasing out club dancers, the stripper aesthetic remained. Jeanette Chaves, who played the lead in “Excuse Me Miss,” a video that made every effort to channel sophistication and class, was styled by lauded stylist and costume designer June Ambrose in a blue, floor-length fur coat. And underneath? A low-cut dress designed by Trosman Churba.

Atlanta’s Magic City icon and current co-host of Angela Yee’s Lip Service podcast, Gigi Maguire, also known as “Your Favorite Stripper’s Favorite Stripper,” had a dance career that spanned from the early 2000s well into the 2010s. Maguire herself has been featured in several music videos, including 2 Chainz’s 2012 track “I Luv Dem Strippers” featuring Nicki Minaj and Big Boi’s “Kryptonite.”

She famously earned $28,000 in just 28 minutes during her “Last Dance,” a farewell performance choreographed for her 2011 retirement. Maguire asserts that the hit show P-Valley was influenced by her story, even being featured throughout season two, further cementing her legacy in the industry.

As far as Black stripper’s influence in the fashion world specifically, Maguire says the throughline is obvious. “As dancers, we were getting butt shots and breast implants, and botox, and wearing weaves down to our butts because that was the aesthetic that we needed to make our money. Now, it’s just everyday girls,” Maguire shared during a video call.

Gigi also points to contemporary brand Poster Girl as a prime example of “borrowed” Black stripper aesthetics, known for selling fishnet bodysuits with clever cutouts, often with hefty price tags. “This is what we used to call ‘pack fits,’” she tells me over a video call. “You could buy that look at a dancewear store or even beauty supply stores for twenty dollars. And now, girls wear that to a regular club or a birthday dinner.”

What were once “pack fits,” named for their packaging, which resembled that of pack hair—are now ubiquitous and priced at ten times their original cost, and can be seen everywhere, including the runways. This shift coincides with the latest resurgence of Y2K fashion, a time when bedazzled denim, body glitter, logo mania, clear heels, and daring cutouts defined the ‘it-girl’ aesthetic. Now repackaged a second time around for the mainstream, these trends have roots in Black strip club culture, where dancers set the blueprint for high-glam, body-conscious dressing long before it hit the runways. Yet, even now, the true origins of these looks remain overlooked, as the cycle continues without proper credit.

Even the billion-dollar athleisure industry owes a debt to the strip club. As Maguire points out, matching leggings and fitted tops were once a telltale day off uniform among Atlanta dancers running errands. “You would look at a girl running into the bank with the same outfit and wonder what club she worked at,” she recalled. What was once a sign of silent solidarity within a niche community has now been absorbed into the mainstream, once again without acknowledgment.

As we engage in the archival work of tracing trends back to their true roots, we have a responsibility to cite accurate sources. When it comes to Black fashion history, that responsibility includes parsing through what’s palatable versus what’s actual. Mariah Webber, a PhD candidate and exotic dancer, expresses that we’ve only just begun to see the influence of sex workers in fashion and music.

Over a call, Webber explains that what she’s particularly interested in is a notion intrinsically tied to morality. “While some women are already considered failures to this project of respectability and morality due to the ways that these histories of sexual othering are informed by slavery and ideas of the Black femme body.” She adds that once you add in the deviant labor category of sex work, “there is additional othering.”

This othering is also evident in divisions of class. “Spandex, Pleasers, and over-the-top hair and makeup were once markers of low and working-class women,” Webber expands. “Stripper aesthetics also borrow heavily from Black trans women and ballroom culture, where many were street-based sex workers. As Jillian Hernandez calls it [in her book] Aesthetics of Excess, the more extravagant the look, the more likely it is to be linked to low-income backgrounds or Blackness.”

The aesthetics of excess, once dismissed as gaudy or low-class, are now celebrated on runways, red carpets, and magazine covers. From extra-long acrylic nails to 30-inch lace front wigs and BBLs, these trends have become mainstream, yet the women who pioneered them, from strippers to Black trans sex workers, remain largely uncredited.

So the question remains: why is this aesthetic only respected when it’s disconnected from the women who birthed it? To honor the legacy of Black fashion history, we must not only acknowledge its origins but also pay our respects to the people who made it possible.