Monica Miller Reflects on Curating the Met & What Black Dandyism Means Now

Monica Miller, Barnard College professor and chair of the university’s Africana Studies Department, was sitting in her New York City office when she received a phone call from Andrew Bolton, the curator in charge at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute. He had one inquiry for Miller: Would she be the guest curator for this year’s Met Gala? Her 2009 book, Slaves to Fashion: Black Dandyism and the Styling of Black Diasporic Identity, would serve as the foundation for both the Gala’s theme and its exhibition, Superfine: Tailoring Black Style.

“He was just like, ‘Hi, I’m Andrew Bolton,’ ” Miller recalled during a recent interview with W. “I was like, ‘What?!’ It was wild.” At first, the offer was almost too big for her to conceive. But she went on to curate an exhibition that explores how style has shaped Black identities across the Atlantic diaspora—particularly in the U.S. and Europe—from the 18th century to today.

The show is broken into 12 thematic sections (with titles like “Champion,” “Heritage,” “Beauty,” “Respectability,” and “Cosmopolitanism”) exhibited across three centuries of garments, accessories, artworks, and photographs—which all interpret dandyism as an aesthetic, an attitude, and a form of resilience.

“ Translating the book from text and visual culture into an exhibition that centers garments and fashion design meant that I was invited to think differently,” said Miller, who specializes in African-American and American literature and cultural studies.

World heavyweight champion Muhammad Ali is fitted for a new suit, London, 1966

Photograph by Thomas Hoepker. Photo © Thomas Hoepker / Magnum Photos

Before Miller’s work could be widely appreciated, however, she first had to get through the Met Gala, the Costume Institute’s spring 2025 celebration, on May 5. Miller was eager to see which stars would bring the exhibition’s themes to life—who would ascend the Met steps on the first Monday in May and leave us all gagged? Watching it all unfold through her curatorial lens, she said she was “deeply moved” by Jodie Turner-Smith’s striking custom Burberry ensemble (the look was inspired by Selika Lazevski, a 19th-century Black equestrian who lived in Belle Epoque Paris).

“People studied, which I thought was so beautiful,” Miller said of the historical research reflected in many attendees’ looks. “As a professor, I was like, ‘Yes! You did the work. Well done.’ ”

During a time when teaching Black history is increasingly being contested—with some states moving to ban critical race theory—Miller is heartened to see early visitors embracing knowledge through fashion. “It was amazing to watch people in the exhibition and get a sense of what’s capturing their attention,” she said of observing folks walking through the show for the first time during the Met Gala. “I’m happy that we’re able to do this on this scale, with this atmosphere of resilience, resistance, and joy. I’m hoping people are taking that spirit out of the space with them.”

The exhibition—which officially opens to the public from May 10 and runs through October 26—has caused Miller to reflect deeply on the relationship between the book and the show, she said. While they are intimately connected, she views them as “cousins.” Still, certain elements were non-negotiable in both. One was Julius Soubise—the first Black dandy of the 18th century to leave a lasting mark on the concept of dandyism.

“He understood that clothing had power,” Miller explained. She felt this idea of employing fashion as a tool for resistance—and how dandyism served as a corrective force—was essential to underscore at the Met.

“A lot of this exhibition has been like a gift,” she said, adding that interacting with the objects featured in Superfine ushered in a new depth of understanding for the history she had studied for so long. Take one of the show’s sections, “Distinction,” which features the Haitian general and a prominent leader of the Haitian Revolution, Toussaint Louverture. Although he receives only a brief mention in the final chapter of the book, Miller explains that the team’s exploration of contemporary art led them to his use of French military dress—later mirrored by Haitian leaders— which both embodied and deconstructed Western authority through fashion.

“We started to see that this kind of military dress is a big deal for a lot of contemporary fashion designers,” Miller said, pointing to how Black menswear continues to reinterpret the military silhouette. Including Haiti’s revolutionary history, she added, allowed the exhibition to build on what she began in the book—demonstrating how clothing can deconstruct colonization and articulate new cultural principles.

Ensemble, Wales Bonner, Fall 2020

Courtesy Wales Bonner. Photo © Tyler Mitchell 2025

Of course, that premise echoes throughout Superfine: Tailoring Black Style, highlighting the evolving role of dandyism. “I think people want to show—and particularly, Black people want to show—pride and presence right now,” Miller said. “Maybe some of the tools that we show in the exhibition are useful in that way.”

Distinction, Gallery View.

Photo © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Still, Miller’s work is far from over. Soon, she’ll be back in the very office where she first took that call from Bolton—the one that ended up defining her year. She’ll return to Barnard College in the fall to teach a course connected to the exhibition. For now, she’s most looking forward to “being quiet for a little bit, doing laundry, and stocking my refrigerator.”

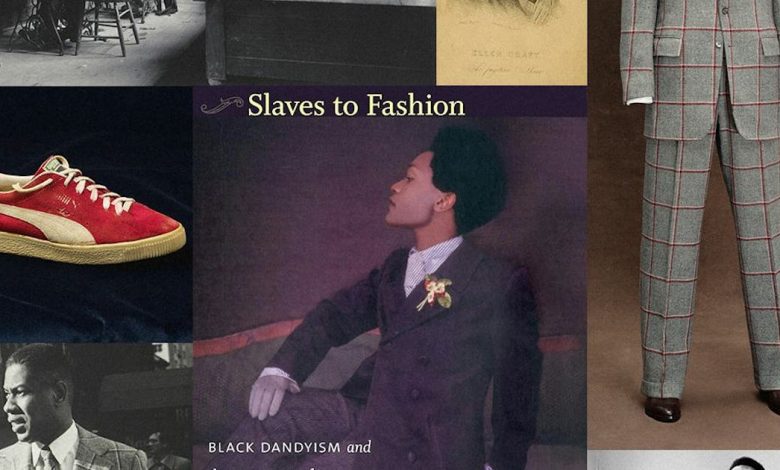

Lead image clockwise from top left: The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Gift of Lincoln Kirstein; Courtesy Internet Archive; Photo © Tyler Mitchell 2025; Photo © Thomas Hoepker/Magnum Photos; Photo © Tyler Mitchell 2025; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, The Irene Lewisohn Costume Reference Library; Photo © Tyler Mitchell 2025; Duke University Press Books.