Baltimore ties at the Met’s ‘Superfine’ exhibit on Black dandyism

NEW YORK CITY — Even on a mannequin and under dim lighting to protect the fabric, the dark coat offers a commanding presence, conveying the regal aura of its owner.

The personal effects of Frederick Douglass, the native Marylander who liberated himself from slavery and became a famous orator and abolitionist, show he knew the power of style to transform. As the most-photographed man of his time, he used his own image to challenge white Americans’ ideas about who a Black man could be.

Douglass and other Baltimoreans feature prominently in a new exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style” examines centuries of Black style through the lens of dandyism. In its original form, the word “dandy” can conjure up white men like Oscar Wilde and Lord Byron — someone who dresses flamboyantly, or perhaps better than his station. But exhibition curator and academic Monica Miller offers a more positive perspective, looking at how Black people have defined themselves and challenged hierarchy through fashion.

Generations of Black dandies, from Benjamin Banneker and Douglass, to later figures like W.E.B. Du Bois and even Mayor Brandon Scott, come from Baltimore.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

“There are definitely a lot of connections to Maryland and to Baltimore in the exhibition,” said Jonathan Michael Square, a fashion historian who consulted on “Superfine.” Located at the nexus between the enslaving South and the “free-ish” North, the state offers a prime location to think about the relationship between slavery and freedom and how that was expressed through clothes.

While Black dandyism became a tool for subversion, it has its roots in oppression, as Miller writes in her book “Slaves to Fashion,” which served as the basis for the exhibition. Wealthy European and American enslavers dressed their human property in fine — albeit sometimes garish — clothing to show off how much money they had.

An item from Baltimore illustrates this point. A purple livery, or uniform, on loan from the Maryland Center for History, sits at the exhibition entrance. According to the center’s chief curator, Catherine Rogers Arthur, experts originally believed the coat was worn by Charles Carroll the Barrister, who built Mount Clare plantation in Southwest Baltimore in the 1760s. Only more recently did researchers take a closer look.

A button fly in the matching pants suggested that the coat was made in the 1840s, yet it featured gold braid and was styled to look like it was from a previous era. “It almost looks like something you could imagine Prince wearing onstage,” Rogers Arthur said. Sweat stains and relatively heavy material indicated that it was probably worn by an enslaved laborer, perhaps someone who stood at the door during a costume party. According to the website for Mount Clare, “livery was deliberately made to look anachronistic to identify the enslaved.”

Square recommended the jacket for inclusion in the exhibition, and the Maryland Center for History and Culture was thrilled to lend it to the Met, Rogers Arthur said. “I couldn’t reply fast enough: ‘Yes, yes, yes.’” Conservators in New York even patched up some parts that needed repair. “It will come back to us in more sound condition than it left us.”

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Another section of the exhibition explores the silks worn by Black jockeys, many of them enslaved. It’s a history the white-dominated racing world has all but forgotten, and is only now getting around to remembering. This month, Baltimore welcomed a statue of George “Spider” Anderson, the first Black jockey to win the Preakness Stakes.

Clothes were also a tool for Black people looking to self-liberate. The exhibition includes runaway notices from newspapers in which enslavers detail the clothing worn by their human property. Once free, clothing became a means for formerly enslaved people to carve out new identities for themselves. The exhibition itself takes its name from the account of Olaudah Equiano, who purchased his freedom and then a suit of “superfine” cloth to celebrate.

Douglass recalled the purchase of his first pocket watch, a feat he hardly could have imagined as a youth when “I did not own myself.” The watch, along with his top hat, monogrammed dress shirts and a pair of sunglasses are all on view in New York.

Nearby sits another loan from the Maryland Center for History and Culture: an almanac featuring the face of Banneker, a Black naturalist and astronomer who was born in Baltimore County in 1731. His attention to detail regarding his own appearance underscored his seriousness as a scientist and upended stereotypes of his time.

Following the end of slavery, influential Black leaders like Du Bois, who lived in Baltimore from 1939 to 1950, used snazzy dressing to telegraph to the world another view of African Americans. A photo in the exhibition shows Du Bois clad in elegant morning dress while visiting Paris for the 1900 International Exposition, where he showed off a compilation of portraits of stylish American Black people. The advocate for Pan-Africanism eventually relocated to Ghana, where he died. The exhibition includes not only his passports, but a 1931 receipt from the cleaners. Good style requires good upkeep.

The Baltimore Banner thanks its sponsors. Become one.

Jazz musician Cab Calloway left his home in Baltimore in the 1920s, later gaining fame in New York for both his music as well as his costumes and oversized zoot suits. While his songs offered a soundtrack for Black dandyism in the 20th century, his style of clothing continues to reverberate to this day.

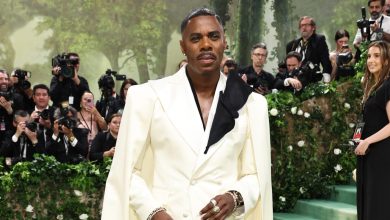

Fashion historian Victoria Pass saw connections between Calloway’s oversized suits and outfits like that worn by Lauryn Hill during this year’s Met Gala. The annual event is a fundraiser for the Met’s Costume Institute, though many people confuse it with the exhibition itself.

Pass teaches Miller’s book, “Slaves to Fashion,” to her students at the Maryland College Institute of Art and says it’s not surprising that Charm City would be well-represented in an exhibition on Black fashion. “People like to get dressed up here. And I think people are really experimental in Baltimore … in ways that you don’t see in other cities,” she said.

She points to Scott, who Pass says “doesn’t dress like your average mayor.” Often seen sporting a brightly colored suit, he’s even received national attention for his hairstyle choices. Though Scott isn’t featured in the exhibition, he offers his own example of Black dandyism in Baltimore, Pass said. Like Banneker, Douglass, Du Bois and Calloway before him, he understands the significance of style when it comes to subverting people’s expectations.

“I think he probably understands he’s going to stick out already,” Pass said. “So why not stick out boldly?”