Mississippi Delta funeral home marks century of service

MARKS – In 1925, a body hung, suspended in a village square outside Lambert, Mississippi. The man, whose name has been lost to time, was the victim of a lynching – one of several hundred Black people killed at the hands of white mobs in the Mississippi Delta in the first half of the 20th century.

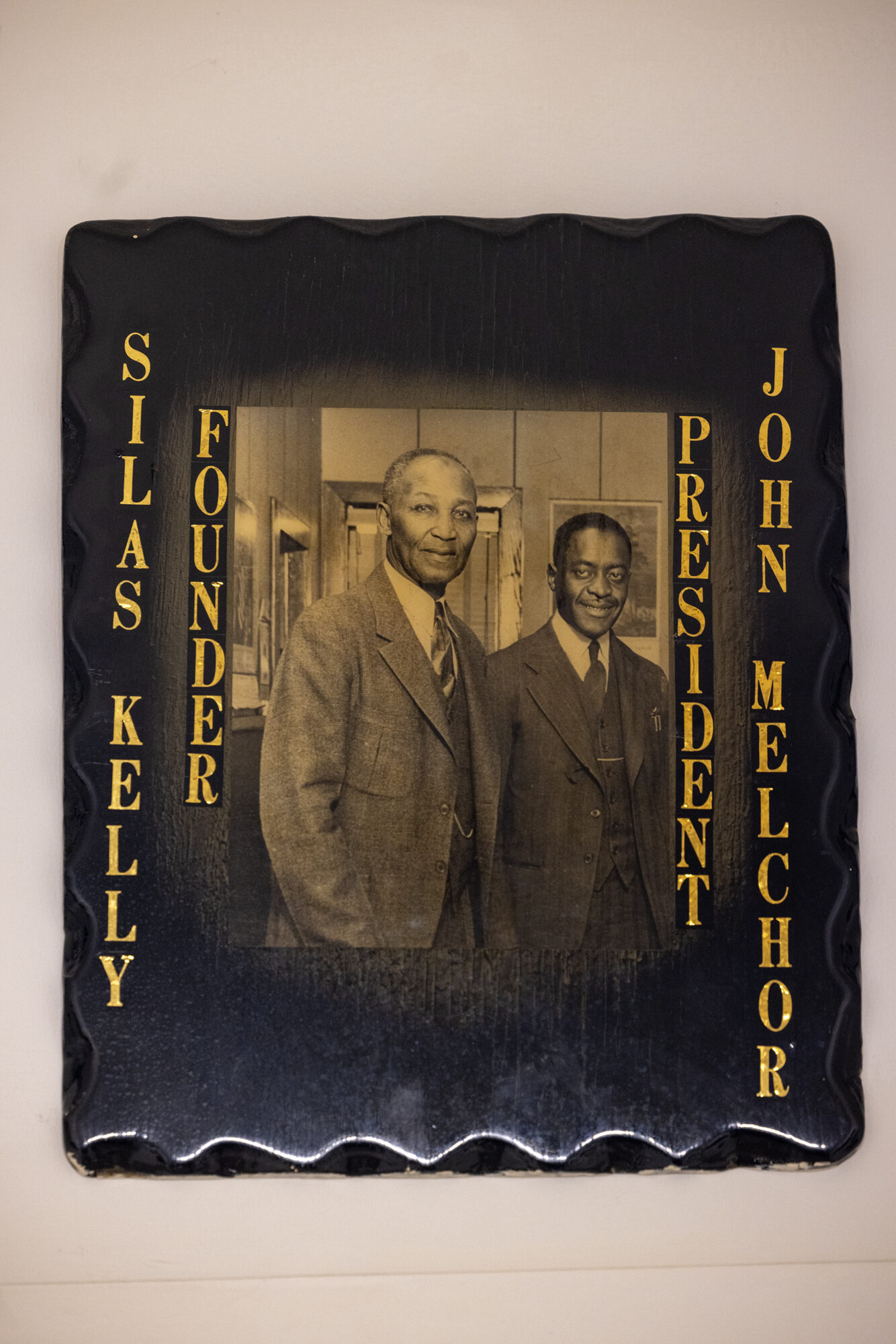

Local Black sharecroppers were afraid to cut the man down. But Silas Kelly wasn’t. The wealthy Black landowner took the body to his home to prepare for burial. The idea for Delta Burial Corp. was born.

Now 100 years later, the funeral home’s mission is the same: provide dignified burials for locals in the Mississippi Delta, regardless of status and income.

Without help from nearby banks, Kelly and his Black colleagues in business and farming pooled their money to form a company. To this day, it remains a business managed entirely by Black stockholders.

Black mourners who sought a standard burial previously had to visit white funeral homes that subjected them to subpar service and inflated costs.

In an oral history, Greenville native and funeral home director Beatrice Huddleston recounted how sharecropper neighbors were often forced to tear plywood from their shacks for a makeshift coffin.

With local wages in mind, Delta Burial offered services on a sliding scale or with small monthly premiums throughout the Jim Crow era, the AIDS epidemic, floods and wars. Its leaders have provided sanctuary for civil rights organizers, hosted burial society galas and organized countless celebrations of life.

The funeral home’s longtime mortician, Woodrow “Champ” Jackson, embalmed Emmett Till’s body at his previous job – and assisted in the transport of the teenager’s body to Chicago. Jackson mentored several morticians who have passed through the Marks funeral home’s screened door.

Today, much of Delta Burial’s clientele still comes from Quitman County, along with southern Tunica County, Coahoma County and Tallahatchie County. Through the business’ inclusion in the National Mortuary program, the funeral home prepares bodies from as far as Los Angeles, Chicago, New York and even East Africa.

This month, Delta Burial Corp. celebrates its 100th year serving Mississippi Delta families. Manuel Killibrew, the corporation’s latest president, credits the firm’s longevity with “reaching out to the community” and “good service.”

A community undertaker

When his father fell ill, Killibrew assisted him on house calls to collect burial insurance. He grew accustomed to his father’s route and soon took it over. He came to appreciate the conversations in neighbors’ living rooms. Every month, he would bring his report and cash to what 55 years later would be his office.

After receiving a large insurance payout from a car accident, he bought his first two shares in the company. He later became general manager and president.

Some aspects of the business haven’t changed. He still makes house calls, visiting grieving families and discussing funeral packages. He still has to negotiate with pastors to keep their sermons and services short enough to make the reserved time at the cemetery.

While the same sales agents for casket companies and vaults still call Killibrew, they now all work for the same company. Many of his suppliers have consolidated, which means higher prices. Memphis, Tennessee, and the Mississippi towns of Canton and Batesville used to have their own casket factories.

Killibrew, who says integrity and fairness are guiding principles, welcomes regulations in the death care industry.

State law requires funeral home directors to show families the actual costs of caskets, vaults, embalming and other services and products. The directors must deposit 85% of money from prearranged funeral contracts into a trust. The money is only released to the funeral home after the service is completed.

At Delta Burial, families have been shown actual prices of products and services as long as Killibrew has led the company.

He said customers often ask for credit so they can pay expenses over time.

“But we don’t turn anybody down,” Killibrew said. “Some bring money every month. Some don’t. But I know we are blessed. We were founded on a religious foundation.”

“You make more on one family and lose more on another. So you still hang on,” he added.

He said a majority of Delta Burial funerals cost $3,000 to $6,000, which is well below the state average of roughly $8,000. He said he has only sold a $10,000 funeral roughly four or five times in his career.

Families are selecting cremation more than in the past for financial reasons. Even Mississippi, which has the lowest cremation rate in the country, saw a 31% increase in cremations from 2019 to 2023, according to the Mississippi State Department of Health.

In his garage, between two Mercedes-Benz hearses, Killibrew pointed to a 4-foot stack of wooden box slats. The most affordable option available for a traditional burial is for his team to assemble a wooden coffin on-site.

“But some still like the show,” he said.

Some families are willing to pay a couple hundred to a thousand extra for a horse-drawn carriage procession. Some opt to rent the Cadillac hearse, which he recently bought in Atlanta for $134,000.

The ancestors

Delta Burial leadership and staff played a discrete role in the civil rights movement. For many morticians who were already embedded in the community, activism was an extension of their service.

On Feb. 2, 1962, former Delta Burial President John Melchor was sentenced to six months in jail for organizing a boycott against white business owners. Two other nearby funeral home directors were sentenced, too. Melchor’s bond was set at $1,500, which would be roughly $16,000 today.

Melchor also hosted the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. at his home in Clarksdale. The two spoke on the telephone frequently and strategized on how to register Black voters in the Delta.

“Until they are stopped, our money, our tax money, will go to the White Citizens’ Council. To be free, you and I must pay and give,” Melchor wrote in a letter to Mississippi pastors and community organizers dated Feb. 14, 1961.

He was fundraising for legal challenges to school segregation cases and cases involving the imprisonment of civil rights activists.

Melchor’s wealth and business success were seen as a threat by his white peers. The Mississippi Sovereignty Commission, a state agency that spied on civil rights activists, kept more than a dozen files on him.

Like other Delta funeral home directors, Melchor’s business suffered as a result of his activism. The Sovereignty Commission connived with local law enforcement to jail his embalmers for operating without a license. While it was standard to leave the license at a business and not in a hearse, law enforcement still fined Melchor and his peers for the misdemeanor when they weren’t at their mortuaries.

Ginise Clement, Melchor’s niece, remembers the family’s first home, which was connected to the morgue and funeral home. She could see from the window in the dining room the caskets lined up. The smell of formaldehyde and embalming fluid would waft through the side door.

She remembers the fear she felt visiting. When she was still a child, Melchor walked her into the morgue to confront her fear.

“You have to be afraid of the live people because those are the ones that can harm you,” Clement remembers John Melchor telling her.

“Sometimes, they would,” she added.

Clement remembers the frequent death threats the family would receive over the telephone. She remembers the strange cars that would follow the family home. She remembers the harassment Melchor’s wife, Ollie Mae, received from administrators at the school where she worked.

“These people were fierce,” Clement said of her aunt and uncle. “I would’ve been scared to death.”

A good day’s work

On Friday evening, mourners departed the funeral home’s chapel for their trucks and cars. The day’s visitation drew to a close. Inside, bouquets of flowers hugged a black casket and colorful lights cast the room in shades of purple.

Shelton Leonard, a 65-year employee with Delta Burial, shut the lid on the casket and wheeled it into a storage room. In another room was the casket with a young woman. Two services were set for the next day.

“I go out of my way to provide service for people,” Shelton said. “I think that’s what it’s about: helping people.”

As the sun set on Marks, creating pink and orange streaks in the big Delta sky, a red pickup, an ATV, a golf cart and two more cars pulled up to a corner near the funeral home. Ulysses Hentz and his brother, Phillip, gathered with neighborhood friends.

They shared tributes to Killibrew and Delta Burial. Killibrew was a teacher for 33 years in the county public schools. He has also represented them on the Quitman County Board of Supervisors for 42 years.

For residents of Marks and Quitman County, economic development has been slow. But Delta Burial has stood as a beacon of success.

Most jobs are out of the county. FedEx has three buses that transport locals to work at its warehouse in Memphis. Others work at the prison in Tutwiler or commute to the many businesses in Southaven.

Crenshaw Rubber Factory, an oil meter, a jean manufacturing factory and a garment mill have all closed in recent decades, taking jobs and families with them. The police department has changed locations at least three times in the last 100 years. But Delta Burial has remained in the same location.

“It’s the oldest business in the community. Black or white. It’s a pillar of the community,” said Ulysses Hentz, whose grandfather’s funeral was recently arranged by Delta Burial.

“If you last that many years, a hundred years, in a town like Marks, you got roots in that mud.”