Why I Refused to Let Breast Cancer Define Me

Juel Copeland’s journey to becoming an esteemed educator and Dean is deeply rooted in her unique personal experiences and unwavering determination. As someone who grew up in a military family, Copeland’s early life was marked by constant relocations and the challenges of adapting to new environments. Despite a turbulent home life, she always found solace in the stability and support of her school.

“School is always where I felt at home, I come from a military background, my mother, my father and my stepfather all served and we moved around a lot,” Copeland shares.

This formative experience inspired her to pursue a career in education, driven by the desire to provide the same safe haven for her students that she once found in her teachers.

Starting as a teacher, she found immense joy and fulfillment in guiding and nurturing her students, which only extended further with the birth of her children, who she credits for further deepening her understanding and empathy.

When her husband retired from the Navy, Copeland’s family settled in the community where she had been teaching for over a decade. However, her two youngest sons faced severe discrimination at school, which led to the filing of a formal complaint.

“The district lawyers said, ‘You know, discrimination is really hard to prove and you’ve proven it like it was very well documented’ and so we yanked our boys out of school and I was not ready to leave the classroom,” Copeland adds. “I was literally the most award, winning teacher my district had ever had. And I was at a high point, but my boys were struggling.”

Choosing to prioritize her children’s well-being over her career aspirations, Copeland transitioned to an administrative role, becoming a Dean without an administrative credential, to ensure her sons had a psychologically safe educational environment.

Balancing a full-time career, studies, and family life was a significant challenge for Copeland. During the early years of her two youngest sons’ lives, she worked part-time to prioritize her family, embodying the role of a full-time mom and part-time teacher.

“I think a lot of times, we expect women to be able to do everything really well. I was not doing everything really well. I was really, really good in the afternoon. But, on the days when I was not teaching…my focus was to spend more time with my kids, so that’s what I did on those days. I didn’t add to my plate during the week so that I could do a lot of things because that’s why I wasn’t working full-time. So, when it comes to balance, I don’t know that you ever truly balance things, but what I did do is I prioritized and I stuck to those priorities,” Copeland shares.

However, in the midst of her thriving career, Copeland was diagnosed with stage 3 breast cancer. The diagnosis was a shock, compounded by the challenges of navigating the healthcare system and the revelation of having dense breast tissue.

“There are so many things I wish I had known. For example, I didn’t know I had dense breasts until after I had already found my tumor at home in the shower. It took me three weeks to get a doctor’s appointment to confirm the tumor,” Copeland says. “Then it took another three weeks to get a biopsy and more time after that for another screening and a biopsy. It took a long time from the moment I found my tumor to the moment I was diagnosed with breast cancer.”

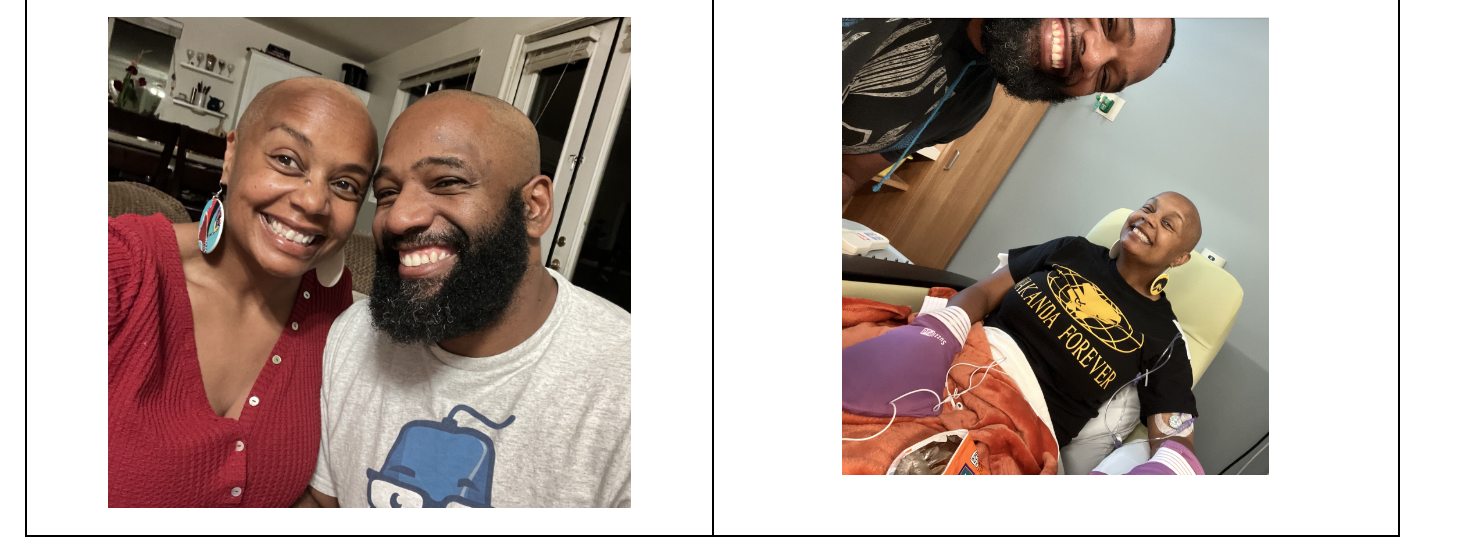

Copeland’s journey through cancer treatment was grueling, involving chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation. Despite the physical and emotional toll, she continued to work full-time as a Dean, drawing strength from her family, colleagues, and students.

“I was diagnosed at the end of March. During that time, my husband and I chose not to tell our kids until we knew more, so we kept the house running smoothly. We were still on a mission. Both of us were in school, working on master’s programs through WGU (Western Governors University). I was also a first-year dean. I had talked myself into that position, so I was figuring things out. When I took over my school, it was the first year they had all three grade levels,” Copeland adds.

Fortunately, Copeland had a strong support system and a school that rallied around her, with staff and students wearing armbands in solidarity during her chemotherapy. Her husband and children were also integral to her support system, sharing in the emotional and physical challenges of her treatment.

“The diagnosis is surreal and feels very isolating. It became a family diagnosis—I don’t feel like I got breast cancer alone. I feel like my husband had the diagnosis as well, and my kids had the diagnosis too. Once it started, it progressed quickly. I started chemotherapy in April and had five months of treatment, including three months of the hardest type, known as the “red devil.” When I got my PICC line put in, all five of our children and my husband wore armbands every day for those five months because I had a band to cover my PICC line,” she shares. “But so did my school. Once I started chemo, I came back to campus, and my entire staff and the students all wore armbands too. It was hard, but I continued working full-time as a Dean throughout the entire chemotherapy treatment.”

Copeland also underwent a double mastectomy.

“When I finished chemo, the entire school rang the bell. And I came in, and they rang the bell loud and clear for me to hear and they celebrated with me. When I finished radiation, the same thing. It’s amazing. I’ve never felt so covered in prayer and love,” she adds.

Despite the immense challenges, Copeland and her husband completed their master’s degrees. She attributes this achievement to the competency-based program at Western Governors University, which provides a flexible and supportive learning environment.

Even after achieving cancer-free status, Copeland continues to navigate the long-term effects of her treatment. Ongoing medication, surgeries, and the psychological impact of her experience remain part of her journey.

“I did 33 rounds of radiation, Monday through Friday, and it was a minefield. Dealing with radiation burns and my melanin-rich skin was difficult. When my hair started growing back, it was a slow process. I wore a hat that said ‘breast cancer’ as a form of armor because I felt people were misgendering me without my breasts and with my hair growing back awkwardly,” she shares. “The psychological warfare and constant grieving were tough to navigate. Even after being declared cancer-free, the journey wasn’t over. I’m still on medication for ten years, which makes me dizzy. People stop checking on you, assuming you’re fine, but the battle continues. I need to schedule a surgery to remove my ovaries due to estrogen-based tumors, which has pushed me into early menopause.”

Copeland’s battle with cancer also underscores the lack of awareness and resources for Black women in similar situations.

“Deciding what reconstruction might look like is also challenging. It’s not just about getting breasts back; it’s about coming to terms with a new body. My reconstructed breasts won’t be the same size, and I’ll look more like a mannequin because I won’t have nipples anymore. Tattoos can create the image of nipples, but I haven’t seen any examples on Black women, so I don’t know what to expect,” Copeland adds.

These experiences have fueled her advocacy for greater awareness and support for Black women navigating breast cancer and survivorship.

“The grieving process continues, even when you’re supposed to be healthy. You need to give yourself space to build the strength to continue. Friends and family may not realize how long the battle lasts, so I had to communicate this to them, which was exhausting. Updating people on social media helped me process and allowed others to understand without needing constant updates,” Copeland shares. “Overall, I’ve learned to navigate the mental and emotional challenges of survivorship. While people want to be there for you, they might not understand the long-term nature of the battle. I had to build stamina and communicate effectively to manage my journey and help others understand.”

Looking ahead, Copeland remains dedicated to her role as an educator and advocate. Through her story, she hopes to inspire and empower others facing similar challenges.